A. Hidden gems in Rome: The original point of view of Leonidas Halkidis | DARIA ARKHIPOVA & FEDERICO BELLENTANI

ελληνικά

Sightsmap is an interactive heat map created by Google that shows the cities with the most photographic activity occurring within them. Rome is the second standing after New York. The map is based on the data from the geo-located tagging, photo sharing mashup: even if not updated, it is reasonable to think that Rome remains one of the most photographed cities in the world.

A screenshot of Sightsmap

From a quick observation on photo sharing social networks, one can identify the main themes and isotopies[1] of the photographic activity occurring within Rome. Sightseeing attractions are king: Colosseum, Roman Forum, Pantheon, Trevi Fountain, Spanish Steps, St. Peter Cathedral, Piazza Navona and so on. Second, one can find pictures relating to eating, dining and drinking in the bars and restaurants of the city, often in the recently gentrified neighbourhood of Trastevere. Finally, there are several images of hidden places reminding a 1960-like Rome with a cinematographic flavour: an old FIAT 500 car parked in a small venue, a Vespa scooter crossing a bridge over the Tiber, a priest riding a bicycle as in the Fellini's movies.

Beside the represented subjects, pictures of Rome follow some specific - we might say stereotypical - principles in terms of angle, colour, light, texture and composition. Sunset light is often preferred. Pictures of ancient monuments aim for symmetry, despite the irregularity of their built forms characterised by the ravages of time. Most of the pictures of the Coliseum from the outside show the part facing the Roman Forum; other sides are rarely photographed.

The photographer Leonidas Halkidis goes beyond these figurative stereotypes by proposing black-and-white pictures of Rome. He plays with cinematographic aesthetics of the most important directors of the twentieth century. Hard light, contrasts, composition - all indicates the inspiration from the movies of Fellini, Godard, Rossellini. All these recreate the spirit of a golden era of the Italian cinema. The Coliseum is represented in tight close-up with a distance that is almost eliminated, the surroundings being set into a universal immediacy. The photos are the texts revealing only the selected meanings to a spectator. Black and white minimalism helps in this attempt. The ravages of time are clearly visible, unlike the stereotypical pictures seen above, edited and shared on Instagram or Facebook. The author deliberately cuts the details related to here and now, he wants to show Rome as a timeless entity where the white sun preserves the shapes drawn in black colours.

The originality of Leonidas Halkidis’s gaze on Rome goes beyond the Coliseum including less known built forms, such as the eleven Corinthian columns of the Temple of Hadrian, which was incorporated into a nineteenth century palace currently housing the Rome's Chamber of Commerce. Some unusual statues are captured through the camera, not the must-see ones such as the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius on the Capitoline Hill, the bronze statue of Julius Caesar near the Roman Forum or the Pietà by Michelangelo in St. Peter Basilica. Among them, there are the remaining parts of the Colossus of Constantine, a statue of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great previously located in a basilica near the Roman Forum: parts of this statue now reside in the courtyard of the Capitoline Museums, as if it were in a metaphysical painting of Giorgio de Chirico or Carlo Carrà.

But the main subject of Leonidas Halkidis’s portfolio are the graves of the Protestant Cemetery (in italian: Cimitero acattolico), better known as the Englishmen's Cemetery, a hidden gem surely not included in the tourist’s “Three days Rome tour”. We can see the Angel of Grief, a sculpture of a weeping angel made in 1894 by William Wetmore Story to decorate the grave of his wife Emily. The creation of the sculpture was described two years later in Cosmopolitan, making it one of the most famous graves. Many prominent replicas can be found across the world (e.g. the Henry Lathrop monument at Stanford University). Its image was also used on an album cover for the metal band Nightwish and in the film The Woman in Black (2012).

Τhe Protestant Cemetery is the final resting place for the English poets John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Keats died in Rome of tuberculosis at the age of 25 in 1821. His grave does not include his name, only an epitaph written by his friends Joseph Severn and Charles Armitage Brown:

This grave contains all that was mortal, of a young English poet, who on his death bed, in the bitterness of his heart, at the malicious power of his enemies, desired these words to be engraven on his tombstone: Here lies one whose name was writ in water.

Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned in 1822 in a sailing accident off the Italian Riviera. His body was found and then cremated on the beach near Viareggio by Lord Byron and Edward John Trelawny, the English adventurer. His ashes were sent to the British consulate in Rome that interred them in the Protestant cemetery. His gravestone presents the inscription Cor cordium (Latin for heart of hearts), followed by a quotation from Shakespeare's The Tempest:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea change,

Into something rich and strange.

In Rome there is also the Keats–Shelley Memorial House, a museum housing an extensive collection of memorabilia relating to Keats and Shelley as well as other English Romantic poets. It is located in the building on the south base of the Spanish Steps, near the Babington’s Tea Room (whose inscription is photographed). The tearoom was founded by two young English ladies who arrived in Rome in 1893 and immediately became the meeting point for aristocrats and noblemen.

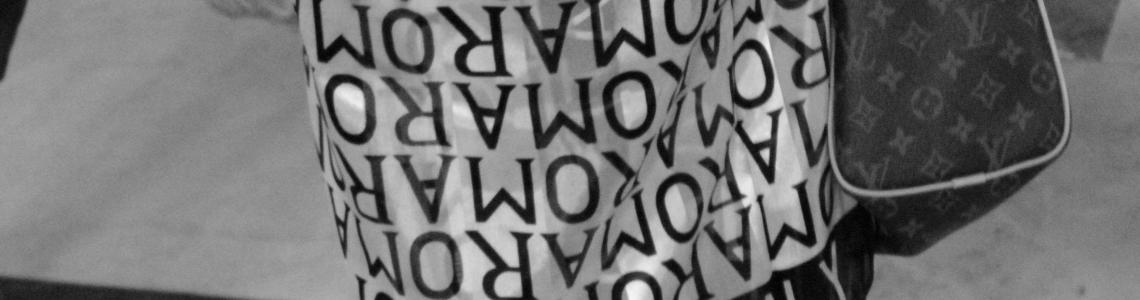

The portfolio closes with two pictures representing two different fashion styles, whose comparison creates a sort of ironic effect: on one hand, a fancy woman with a silk skirt presenting the word ‘Rome’ all over and, on the other, a person in white jeans but without t-shirt and shoes sunbathing on a bench.

B. Roma | LEONIDAS HALKIDIS

References

Eco, U. 1984. Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Eco, U. 1992. Interpretation and Overinterpretation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Greimas, A.J. 1987. On Meaning. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kourdis, E. 2012. Semantic isotopies in interlingual translation: Towards a cultural approach. Journal of Theory & Criticism 20. 105-116.

Pozzato, M.P. 2001. Semiotica del Testo. Metodi, Autori, Esempi. Rome: Carocci.

[1] An isotopy is a repetition of basic meaning traits reiterating their content in texts and thus ensuring coherence and homogeneity to texts (Greimas 1987; Pozzato 2001; Kourdis 2012: 106-107). Umberto Eco (1984: 189-190) expanded isotopy to include “diverse semiotic phenomena generically definable as coherence at the various textual levels”. Eco (1992: 65) replaced the concept of ‘repetition’ with the concept of “direction” defining isotopy as “a constancy in going in a direction that a text exhibits when submitted to rules of interpretative coherence”.