There is something unique about art making that takes place underground—in drain tunnels, bunkers, or abandoned crypts. Dark, cavernous spaces offer urban artists the freedom to experiment with forms of expression apart from, but not excluding, the painting or marking of surfaces.

One such expressive form is the practice of lighting fires. In an underground setting like a drain tunnel, fires become visual art. Urban explorers pour petrol into flowing storm water or over a tunnel’s surface to create different visual ‘performances’, each one a fleeting and ephemeral ‘event’ [1].

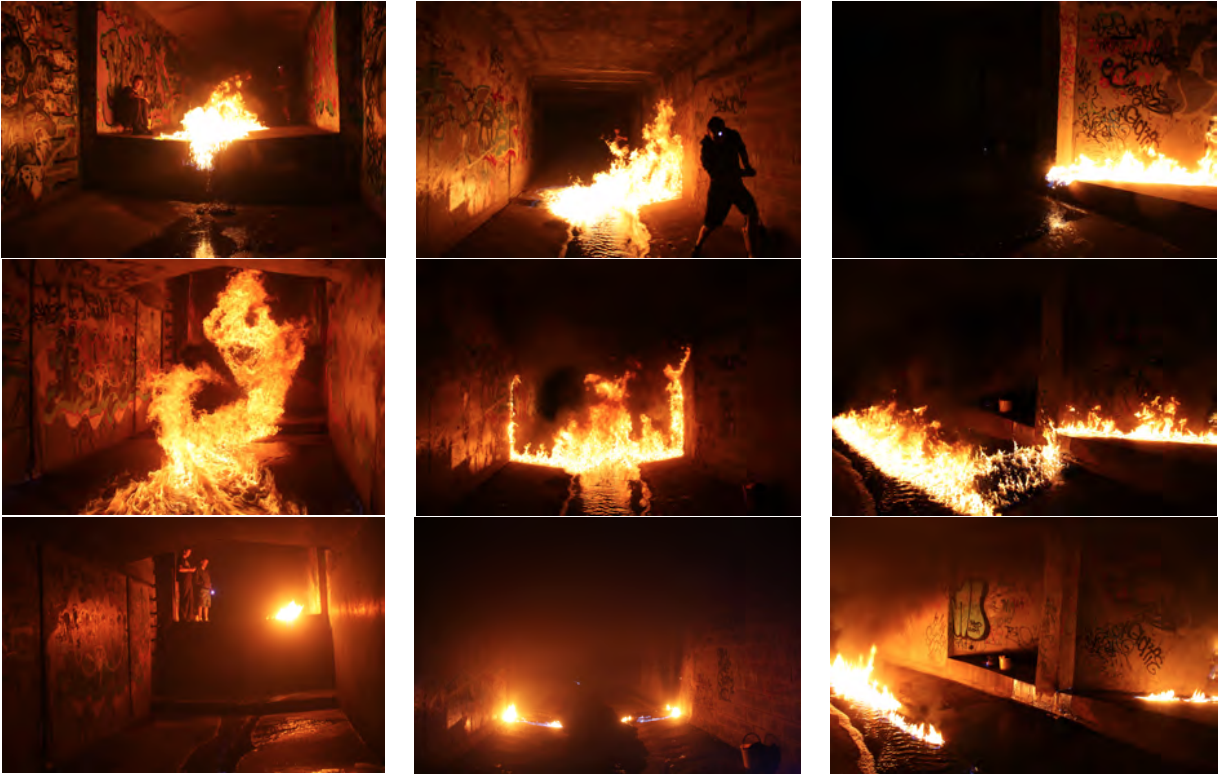

This series of research photographs document Panda’s creation of three ‘fire displays’ in a storm water drain in Melbourne, Australia. The first row of photographs was taken shortly after ignition, the second row at the peak of the fire, and the third row at the point of its dissipation. Each ‘creation’ last only a few seconds but takes the drain environment from darkness to intense light and back again, temporarily sucking all of the available oxygen out of the space.

Panda describes his practice of fire setting in psychological terms:

I used to light large, elaborate fires in drains as an adolescent. Pyromania is categorised as an anxiety disorder, but this, I feel, is overly simplistic and politically motivated. To go into why I lit fires would be to write an extensive auto-ethnographic, psychoanalytical piece about my experience of growing up in the world. Maybe it is enough to say that there was a vast, stormy ocean of anger within me, very much suppressed, which motivated me to create these huge displays. I felt like this raging anger within me could have destroyed the world, but I didn't want to. I chose storm water drains because they were safe - concrete and water. The biggest risk was to myself. Seeing the fire take off, possessing such life and energy, satisfied something in me. It seemed to reflect the anger I felt inside me, as I was depicting it, so I could get to know it better. It was always ephemeral art - a huge roar of energy, then dying off and in a brief moment gone - something reflecting my experience of emotion and a microcosm of a human life.

My understandings of Panda’s practice are geographical, derived from the logics of a Deleuzian ontology [2]. For Deleuze, the ‘real’ is temporal. Events never reproduce themselves, because they are always new. Events don’t create outcomes; they create difference because they occur by accident or by chance [3]. Being is always secondary to ‘becoming’ because life is always-already transforming itself [4]. Within the constant flow of events, however, are singularities—moments or points of tension that are unique [5]. Panda’s displays are singularities of immense proportions, existing for a matter of seconds before rapidly diminishing [6].

An important function of contemporary art practices is bringing audiences into contact with notions of space, time, and subjectivity. It is the precarity of space-time that makes our world so fragile. While process always entails loss, creativity without purpose is the principle of novelty [7]. The world continually makes and remakes itself as we are propelled into a future that always remains open. Of this stubborn fact, Panda’s practice is a profound reminder.

Notes

- Deleuze, G. (1990). The logic of sense. [Translated by Mark Lester with Charles Stivale, Edited by Constantin V. Boundas]. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition. [Translated by Paul Patton]. NewYork: Columbia University Press.

- Lawlor, L. (2012). Phenomenology and metaphysics, and chaos: on the fragility of the event in Deleuze. In Daniel W. Smith and Henry Somers-Hall (eds). The Cambridge Companion to Deleuze. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. [Translated by Brian Massumi]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Grosz, E. (1994). Volatile bodies: towards a corporeal feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Massumi, B. (1996). Becoming-deleuzian. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14, 395-406.

- Whitehead, A.N. (1978). Process and reality (corrected edition). New York: The Free Press

Candice P. Boyd is an artist-geographer at the School of Geography at the University of Melbourne, Australia. She is author of Non-Representational Geographies of Therapeutic Art Making: Thinking Through Practice, forthcoming with Palgrave Pivot in 2016.

Panda is a multi-modal artist and creative arts therapist who chooses not to be identified by name in this article due to the nature of the activity.