Click on any image to view gallery

This article presents small change, a group exhibition curated by Manchester based curator Sevie Tsampalla at AirSpace gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, in November-December 2013. A selection of works and projects presented in the exhibition is discussed in the following lines.

The exhibition examined urban change through the lens of art and collective action. Inviting individual artists and collectives, the curator attempted to connect diverse practices that research the experience of the city, its representations and possible re-imaginings.

How do art and coming together in public space affect change in contemporary cities? small change was a curatorial exercise aiming to research the city as a space of artistic and political transformation. Juxtaposing artworks to audiovisual material by collective projects and opening a dialogue with the city of Stoke-on-Trent through an intervention in public space, there was an effort to create a link between the gallery space and spatial practices in real urban settings. What kind of a curatorial practice is able to translate in exhibition formats art practices that relate to urban changes and how does one curate change?

From the idealised depictions in renaissance paintings to the modernist urban utopias, art has always been drawn in exercises of re-imagining the city. Contemporary artists engage with urban life in ways that cross boundaries between art, activism and community building. Reclaiming public space and working together with communities, artists act as placemakers and catalyse collective action. The self-organised systems which they initiate are often quicker than large policy schemes to address the urban urgencies resulting from economic, social and political changes. Operating on local scales and low budgets, their public space interventions mirror the inventive problem solving (using own resources and improvising solutions) of local people in informal cities around the world. As much as it is about objectives and action, change can begin with improvisation and imagination.

The exhibition drew largely from the book Small Change by architect and urban planner Nabeel Hamdi. Outlining the principles of good practice when it comes to placemaking, Small Change is about a community-based approach to urban planning, which starts with listening to real needs and observing the intelligence of places and people. [1] Small interventions with immediate effects and strategic potential can lead to meaningful and long-lasting changes. In a well cited example from the book, “Building a bus stop in a slum leads to a community growing around it.” [2]

Looking at the city both as we experience it and as we re - imagine it, the exhibition posed the following questions: Where do art and placemaking meet in contexts of real urban changes? Can change be located in the sphere of the urban imaginary?

The act of balancing between (utopian) visions and real urban challenges was taken as a starting point for the research, but not in order to seek consensus. The premise was rather, that both the ‘hard’ city of real data and the ‘soft’ city of emotions are constituent elements in the processes of placemaking. “The city as we imagine it, the soft city of illusion, myth, aspiration, nightmare, is as real, maybe more real, than the hard city one can locate in maps and statistics, in monographs on urban sociology and demography and architecture”. [3] Beyond the big numbers of growth and development, the narrative of urban change can also be told through people’s voices and visions of the places they inhabit.

The ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ elements often appeared interwoven in the works of the exhibition. Scale models, signs, mind maps or measure tapes are appropriated by the artists in ways that suggest it is possible to think differently about our city making tools. Without necessarily rejecting their ‘technical’ properties, such objects become vehicles for articulating an alternative relation to urban space. Sharing an interest in the representation of change, the works might start with simple observations or modifications, but soon depart from the actual to arrive at a space of potentials.

Claire Weetman’s Reversal of flow, an intervention in public space, took place on Tuesday morning, 19th of November 2013. Having observed that some bus stops became devoid of their function as a result of a newly built bus station, Weetman focused her research on the redirection of bus routes in Hanley. Ten six-metre-long arrows made of felt were laid onto the road surface. Pointing north at first, their heads were subsequently moved to point south, marking how the movement on this street had been altered. The artist traversed the road a few times in order to lay the arrows – her repetitive and persistent movements became a physical way of measuring space. Their blue colour referenced the standard 'one way' signs and the diagrams issued by the City Council to communicate the re-organisation of the road network.

A short-lived spatial drawing, Reversal of flow visualised both the past movement at Stafford street, absent but still traceable in the empty bus stops, as well as the, not visible yet, future (at the time of the intervention) flow. The impact that this change has on the experience of the city is still in progress. Its transformative potential was perhaps momentarily captured in the artist’s action. Beyond this layer, the act of reversing prompts reflection on the hierarchical communication flows that define public space, and our potential to renegotiate them.

In the constantly changing city setting communication is about flow, movement and transportation. [4] Sign-literacy is a precondition for navigating it. Signage systems (maps, signs, boards…) inform, guide, or prohibit us, with the apparent aim to make the cityspace more legible. Much information in public space is accepted without questioning and communication is more than often a top-down process. If earlier urban planners saw it sufficient to educate city dwellers on how to look at or read the city [5] the question that is now more pertinent to ask is: Can we be co-authors of the city’s text? In Small Change terms, how can we participate in the processes of (re) designing spaces?

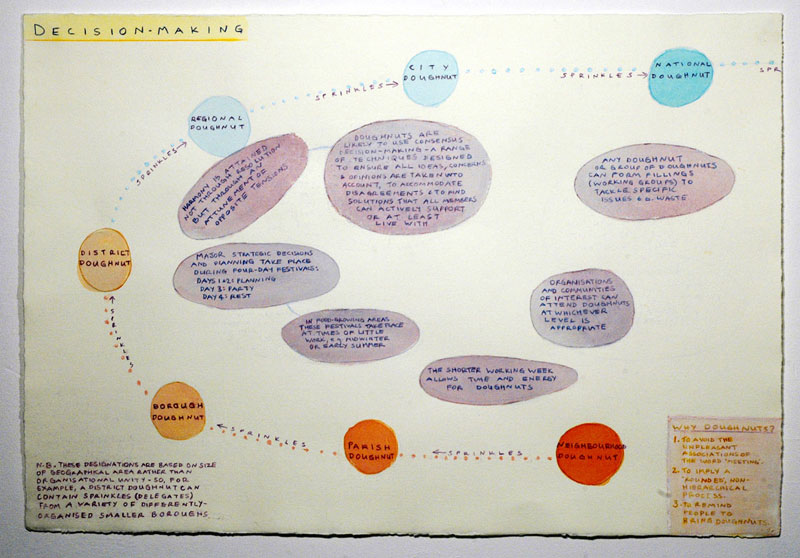

A public space that is planned collectively through practices of commoning is sketched in a series of mind maps created for small change by Jane Lawson. From cars to software and from food to energy, goods and resources are shared, managed collaboratively or exchanged between citizens. The artist’s ongoing investigation on alternative forms of a post capitalist social organisation looks into existing models but often attempts a bold and idiosyncratic revision of them. For example, a set of measures, such as minimum and maximum incomes, local currencies and reasonable usage of natural resources are discussed in the frame of the steady-state or degrowth economic proposals, which question the conventional development indicators of productivity and consumption and oppose a limitless economic expansion. [6]

Humour and imagination provide equally important tools of social restructuring in this study in grassroots democracy. Decisions are taken by working groups of “doughnuts” during 4 day festivals that include a party, a rest day and real doughnuts! The artist does not forget to include even the simplest gains resulting from self-organised urban practices: “Food grown locally is tasty!” Although they do not always appear as revolutionary, such small ‘acupuncture’ points, as Lawson calls them, can function as the guiding principles for the fundamental changes needed in the paradigms governing our systems, and our collective imagination. [7]

The collectives’ contributions opened the exhibition further to the space of potentials, but this time locating it in real urban sites. The research departed from the principles of Small Change and focused on urban areas of redevelopment, regeneration (Silwood estate, Brussels, Cheetham Hill) or social emergency (Athens). Three criteria based on the book defined the selection: enablement, togetherness and effort. The selected projects mobilise multiple agents (artists, residents, local organisations) and through a common effort enable them to respond to changes or work towards positive change. Creating interfaces between planning, art and activism, they participate in a broader framework of practices that ‘consider the production of space as a collective, dynamic and political enterprise and push transformative social change’. [8] The changes that they aspire to targets not just their immediate environment, but feed the debate about what is public space, and where the interaction between the top down and the bottom up happens.

The DIY Common that the London based collective public works is developing since 2013 in Cheetham Hill is testing the possibilities of creating a new type of common. Dating from 1886, Cheetham park, commonly known as Elizabeth Street Park, was once the epicentre of a vibrant community around it. After the slum-clearances in the area, it became a bit neglected. A joint effort between residents of the area, public works and Buddleia, a North West cultural agency, the project seeks to inject new life, both natural and social, in the park. Dye and herb gardens have been added, in order to maximize the park’s potential as a natural resource, while workshops of gardening, natural dying and cooking with plants gathered from the park create new community spaces in the area. Products from these activities are served in a café, whose mobile structure was designed specifically for the project. There are plans to collaborate with local schools and agents in order to restore the park’s viewing shelter which hosts the café structure. The process is an exercise that will eventually lead to the residents managing the café and the park themselves. Together with its users, the DIY Common looks to restore not only the park’s physical, but also intangible heritage, extending the possibilities of commoning from the rights to land use to the rights of deciding together and collectively designing the city.

Simple initiatives can transform everyday spaces to political ones, contributing to the democratisation processes that allow societies to come together. The projects in small change incorporate simple acts or "arts of doing", like walking, cooking, and gardening in the relational processes that they put forth. Tactics are simple acts that can challenge or disturb the institutional strategies that define the city and life in it. [9]

The Athens collective Nomadic Architecture uses walking as a means of re-establishing the relation to the city of Athens and its changing physical and human landscape. Their walks are statements about the city’s current situation and a call to respond to it. A video documenting a walking action from the occupied Embros theatre to the area of Exarheia ran during small change. The streets where the action took place constitute the old core of the city and host a.o. small shops by migrants or their informal gatherings and activities. The area has known an increase in arrests and police forces, as large-scale occupations and hunger strikes had taken place by those seeking legalisation and a temporary 'home'.

Walking slowly and aimlessly is reserved for tourists, dog walkers, children, the old, and is sometimes suspicious [10] In the centre of Athens, it is also the migrant, the homeless, the day labourer that disrupt the fast walking paces of the city. Nomadic Architecture’s walking actions interrupt the narrative of displacement happening in the centre of Athens. Poems are recited, flowers are given to passers-by, goods and stories are exchanged, a shared experience of the city takes shape.

Change involves a projection in the future, implying an effort to make something different or better. In the exhibition change was articulated in both spatial and social terms, echoing their interrelation as constructing elements in the production of urban space. By now, we have come to understand that (public) space is not just the backdrop of change, but where change happens. (Soja in Lindner 2006, xvii)

small change: an exhibition curated by Sevie Tsampalla (GR). artists: Jane Lawson (UK), Noor Nuyten (NL), Lauren O’Grady(UK), Claire Weetman (UK). collectives: Buddleia / public works (UK), Network Nomadic Architecture (GR), Plus-tôt Te laat / Quartier Midi (BE), Spectacle / Silwood Video Group (UK). AirSpace Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent. 8.11 - 7.12 2013

A complete overview of the exhibition is available on http://issuu.com/small.change.epilogue/docs/small_change_epilogue

SEVIE TSAMPALLA is a Manchester based curator. Her practice researches collaborative processes, public space, as well as intersections between art and broader modes of cultural production. Her most recent exhibitions were small change (AirSpace gallery, Stoke-on-Trent 2013) and Some Misunderstanding (Castlefield gallery, Manchester 2013).

Endnotes

[1] Hamdi, N. (2004) Small change: the art of practice and the limits of planning in cities. London: Earthscan. see page 17.

[2] Ibid 73

[3] Raban, J. (1974) Soft city. London: Hamish Hamilton. See page 2.

[4] Burd, G., Drucker, S.J. and Gumpert, G. (2007) The urban communication reader. Cresskill, NJ, Hampton Press, see page 7.

[5] Lynch, K. (1960) The image of the city. Cambridge: The Technology Press & Harvard University. see page 117.

[6] Santos R. (2013) Spatial Assemblages. The production of space(s) beyond the imperative of growth. In: Jossifova D. (ed) 2013) Times of scarcity: Reclaiming the possibility of making the city. Glasgow: Newspaper Club. See page 6.

[7] Martinez-Alier, J., Pascual, U., Franck-Dominique, V., and Zaccai, E. (2010) Sustainable de-growth: mapping the context, criticisms and future prospects of an emergent paradigm. Ecological Economics, 69, pp. 1741-1747. See page 1742.

[8] Santos R. (2013). See page 7.

[9] de Certeau, M. (1984) The practice of everyday Life.(Transl. Steven Rendall) Berkeley: University of California Press. See page 35.

[10] Luiselli, V. (2010) Sidewalks. (Transl. Christina MacSweeney) London: Granta. See page 33.