español

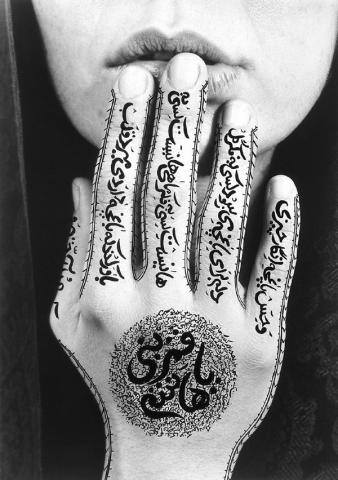

Shirin Neshat writing Persian poetry on the image of a young Iranian. Series Patriots

All images published here are courtesy of the artist.

Curator Catherine David[1] ensures that exile is about attitude. This attitude is what led Iranian artist Shirin Neshat to what is one of the most stunning artistic careers in the field of photography, video and film today. As a woman and an exile, Neshat has survived the nostalgia suffered by those that live a long way from their homeland and she has reconstructed her memories from the perspective of a person who has developed her own identity by looking for herself between her origins in Iran and her destiny in the USA. Between a country anchored in prohibitions and one that offers a present and future that is safe and promising.

Shirin Neshat is now internationally known for capturing through photography and video the emotion of exile and the difficult role of women in Islamic society and the differences between the rights of men and women in her country, and throughout her long career she has shown and denounced those things that are forbidden to show and report on in a Muslim country like hers. After her first trip to Iran after sixteen years of exile, she began her first series of photography reports: Unveiling and Women of Allah in which she reflects on the ideology of Islam and the plight of women in her country. Since Iranian women were obliged to wear the hijab in 1979, more than thirty years have passed by and the situation has not changed. At that time women revolutionaries accepted the hijab not because they thought it would contribute to the recovery of their own culture, but as a symbol of revolutionary identity and an anti-Western model. Probably this is why most of the images of Unveiling and Women of Allah belong to young women, because it is through the younger generation that the artist reflects the feminist movement that is shaping a new generation determined to fight to defend their rights. Brave, bold women that don't have a place for the word “discouragement” in their lives...., only showing the one part of themselves that can be shown in public. It is this that Neshat uses as a support for her artistic creation to denounce with beautiful Persian calligraphy for Muslim women the spoken word is only free in private.

The world's problems can be made visible through photography, especially when it comes to places with a censorship like Iran, a country whose society doesn't want to turn its back on modernity, and that transforms its artistic creation in subtle metaphors of everyday life. Most of Shirin Neshat's photographs are in black and white on gelatine plate, with calligraphic inscriptions in various sizes on photographic paper, which in some cases are very big, in editions of three, five or ten copies, numbered and signed.

Anna Casanovas[2] explains that photography is not a mere photochemical reproduction of our optical perception and as such it should not be limited to being a document that authenticates history, but a (re)creation of a visible world. This is exactly what Shirin Neshat does through her pictures with Persian calligraphy, recreating the current situation of women in Iran to make it visible to the world.

Some of the texts written in Farsi are verses and religious quotes from the Koran that refer to the duties and obligations of Muslim women to God but also to men, genuine patriarchs characterized by the opportunistic way they read the Koran. That's why these quotes are used by the artist in a critical way to protest against the loss of rights in Iranian society. In terms of Iranian society in general, and women in particular. In her country, you cannot talk about rights, a little-spoken word, especially if one is born a woman.

In some photographs from Women of Allah, the calligraphed verses are texts by Forough Farrokhzad[3], an important woman in Iranian literature. She was the country's first female poet to be publicly recognized and considered one of the bravest and transgressive writers in Iran's new 20th century literature. Farrokhzad dared to write poems about her experiences, love, feelings and sex, creating a real challenge to the Iranian clergy. With her attitude and autonomous and free lifestyle, she brought into question the traditional values that had always been associated with women, and that is why her work was unjustly described as immoral and indecent, and her books banned from being published. However, Iranians that had read the poems of Shahnameh, شاه a very well-known Persian epic written by Ferdowsi[4], were not scandalised by the daring and provocative tone of the verses by Forough Farrokhzad.

(Left) Women of Allah (3), (Centre) Untitled, (Right) Guardians of Revolution

Iranian poetry has always been deeply subversive, and the fearless and active profiles of the heroines of some old Iranian poems had broken moulds and changed roles, with women adopting an unusual prominence that had always been given to men. This feminine role was immortalized by authors like Ferdowsi فردوسي, Gorgani گرگاني or Nizani شمار ميآيند, some thousand years before Farrokhzad, and this means that Iranian society was accustomed to the sensuality that flowed in the best work of this fiercely contemporary poet. In Iran, love for and the veneration of poetry is not just a tradition, but a real necessity that has been integrated over the last century into the different art forms because it is truly innate in Persian culture.

Answering the question about how important poetry and calligraphy were in her country and work, Shirin Neshat said:

Poetry and calligraphy are innate in Iranian culture. I like poetry because it has the potential to be metaphorical, and for us Iranians, metaphorical language is essential. It has been used for many years and today it is used by artists and visual artists, because it provides the opportunity to "say what is forbidden to say" without being censored, and it allows you to make statements between lines in a country where we are forbidden from speaking out, especially women. That's why it is logical that the halo of poetry is found in my work because it's part of me, my personality and my culture. It's part of my art and comes through easily when I'm creating. I like to count on Iranian poetry, because I know that it's understood by my people. In terms of Farrokhzad's poems, they are very necessary for my work for explaining my feelings and the character of my people. She was an amazing poet who wrote about forbidden things for a woman, like love or desire.[5]

By recreating Farrokhzad's verses, Neshat finds the tranquillity that her memory stole away and writing these on the faces, hands and feet of the female figure, she can express her feelings about the correlations between tradition-modernity, East-West, men-women, which at the same time is associated with the tension between freedom and oppression, the pure and impure, madness and reason, and these extremely dualistic expressions have been rooted in Persian culture for centuries. Using parts of the female body as controversial space shows the traces of humanity that are hidden between image and writing, questioning the peculiar link between politics and religion, terrorism and fundamentalism, anger and devotion ... contrasts/contradictions that still characterize today's society in her country.

In some of these images, the barrel of a kalashnikov brings clear tension to these women, whom Neshat uses to denounce the ambiguity between the spiritual and political spheres in Iran introduced by Khomeini since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. A revolution in which women participated actively raising awareness amongst the female sector about the inequalities in their society. In these images, in which the artist sometimes appears with her son, she tries to introduce these post-revolutionary women as they were at the time she visited Iran after years of absence: armed and militant women who fought alongside men for the revolutionary ideals of Khomeini.

(Left) Untitled, (Centre) Speechless, (Right) Allegiance with Wakefulness

In some of Neshat's photographs she also uses poems by Tahereh Saffarzadeh[6], a well-known radical Iranian writer and poet. With an Islamic yet universal vision, Saffarzadeh described herself as a true fundamentalist, a staunch advocate of Khomeini and fervent follower of his philosophy and idealism. Her verses, with highly political content, were used by Neshat to show the concerns of militant Muslim women who at the time supported the new leader of the revolution and took up his discourse of sacrifice and martyrdom with the idea of defending their country from the tyranny, despotism and abuse of power of the Shah.

Her latest photographic series presented in 2011 in her New York Gladstone Gallery, is titled The Book of Kings. Some photographs in this series as well as some of Women of Allah, were presented in June 2013 in Madrid at an exhibition curated by Octavio Zaya, Escrito sobre el cuerpo (Written on the Body) at Fundación Telefónica.

With the exquisite skill of a cartographer and the minute precision of a surgeon, Shirin Neshat converts something that is very individual into a global thing, political issues into something personal. Putting her particular calligraphic trail onto the photographs masterly brings together poetry and image, humanism and science. The Book of Kings communicates deep emotions and it places us both at the time of the Revolution (1979) in which men and women participated and defended the ideals of freedom, and also during the riots that took place in June 2009 after the electoral fraud of former President Ahmadinejad. Past and Present. History repeats itself.

The Book of Kings is a series of photographs, with Farsi calligraphy and beautiful drawings from the pre-Islamic history of Persia inscribed on the developed image. As in her first series, this calligraphic foray is the link that binds Neshat with her country, with tradition, with popular culture and ancient Persian history. And it does so through her individual language of imagery and poetry. Meanings and significant cultural writings on the bodies of the characters in this series; Persian manuscripts and drawings illustrating the history of the Persian people before the Arab invasion (640) based on the writings of Ferdowsi in his epic poem Shahnameh also called The Book of Kings. A symbol of the integrity of the people and an allegory representing the defence of mankind against tyranny and oppression.

The Book of Kings seems a personal journey through his Islamic heritage comes to current events in Iran. It.is probably her most political work so far, but despite its directness and strength, Neshat is agreeing with a humanism that leads to a questioning of the motives of the senseless violence provoked by contemporary conflicts, and she reflects on Iranian history, culture and society and recalls the Green Movement of June 2009 when the Iranian people took to the streets in an absolutely peacefully way to defend their rights. The series is grouped into three sections titled: Masses, Patriots and Villains.

Masses is a series of 45 photographs of distressed faces; the faces of those who participated in the protests to defend democracy in their country. People of all ages and conditions, from the elderly to the youth generation. Men and women. Oppressed people like Omar, Ghada or Ahmed, whose expressions denote worry, anxiety and sadness. With them, Neshat pays homage to the powerless.

(Left) Omar, (Centre) Ghada, (Right) Ahmed

The Patriots group presents a series of head-to-midriff shots of people looking straight at the camera with their right hand over their heart as a symbol of their loyalty to the country. There is a clear expression of pride, dignity, courage and commitment in their faces. Dressed in black and inscribed with Persian poetry on their skin, Patriots remembers those Iranians who have been persecuted, punished by imprisonment by their ideals or even death for defending the freedom of their country. They are the faces of young men and women that are very critical of their country's system of government. Are faces of activists, human rights defenders; faces intense with expressions reflecting challenge but also fervour and devotion. Their look is sober, peaceful and quiet, perhaps hopeful.

Finally, three photographs that make up the Villains series. Three images of serious, grave, masculine men even to the point of exaggeration. Full length pictures, facing straight on, standing or sitting with bare torsos and feet, the villains are men with a severe and insistent gaze, that brim with self assurance, dominance and absolute control. The older man, who goes by the name Bahram, is a man whose indolent gaze continues stubbornly over the traces of time and old age. There are rings of fatigue under his eyes, but his inquisitive and suspicious gaze seems unfathomable, as is the fate of some of the disinherited...

In this series, calligraphy has been replaced by images based on literary illustrations. Images that tell of epic wars, warriors riding high with their spears up, archers firing their arrows, bloody decapitations that reinforce the message of violence, whether religious or political, which Neshat uses as metaphors for the current situation in Iran. Red is the colour that stands out in these black and white photographs, edited in impressive large format images. It is the red blood of the martyrs of ancient Persia that evoke contemporary martyrs. The Iranian feelings of ancient Zoroastrian Persia have been passed down through the centuries with the powerful concept of Persian identity so clearly detected in Ferdowsi's Shanahmeh, and this concept that Vali Mahlouji[7] has called 'Iranianness' continues to be present in the contemporary Iranian artist. Characters change, times change, but feelings do not.

(Left) Bahram (2012), (Right) Fragment of Bahram

Two fragments of series Villains from The Book of Kings

Through photography, Neshat addresses the especially contemporary conflict in her country, providing evidence of how Iran's theocratic government is using double standards, with clear differences when measuring the principles of human rights. And she does this using characters and settings which, although specifically Iranian, in the end take on a universal feel. No matter if you are western or eastern, Christian or Muslim, male or female, because the codes to interpret the message are clear and direct and they can be understood by people from different languages, cultures and religions.

Shirin Neshat has the self-confidence and an ability to stay firm, adapting to anything new without ever losing sight of who she is and where she comes from. In her, there is a powerful desire to start again with links to the old, despite knowing that she will never return to Iran in any definitive way because her life is now in the West. But even from the distance and despite being fully integrated into another country and culture, she remains the daughter of the country she left behind, keeping her language alive with words and maintaining its memory.

Carefully observing the work of Shirin Neshat we see, beyond photography, video and film, in other words, beyond art, that there is the desire to recover the vestiges and memories of her past. Her need to use poetry and calligraphy in her work is a sincere desire to find her roots again. Her motto is not a rule of life. It is a requirement of honesty.

[1] DAVID, Catherine Paris, 1954). Doctored in Linguistics, Literature and History of Art at the Université de la Sorbonne. Has been Curator at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou and Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume (1990-1994) Artistic Director for Documenta X in Kassel, (1994-1997). Director of the long-term project Contemporary Arab Representations which began at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona 1998. Curated in 1999 XXIV Biennial of São Paulo. Between 2002 and 2004 David was Director of the Witte de With Center of Comtemporary Art in Rotterdam in the Netherlands. She is currently a fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin.

[2] CASANOVAS, Anna. Degree in Modern History. PhD in Art History from the University of Barcelona. In L’evolució de la mirada. El segle dels audiovisulas” in Materia d’art. University of Barcelona. 2001. Nº 24. Pag. 305.

[3] FARROKHZAD, Forough فروغ فرخزاد, (Tehran 1935-1967) Her poetry with strong political and social content against the repressive regime of Shah Reza Pahlavi was absolutely clear. A traffic accident at the age of 32 caused her death, but no one believed it was a simple accident. Along with Nimá Yushy, Sorhab Sepehri and Ajaván Saless, a group of innovative writers of her epoch, Farrokhzad used popular expressions in her poetry. Impressed by the life of this women poet, Bernardo Bertolucci made her life into a biographical movie. She was also one of the first filmmakers, shooting several short films of which Khaneh siah ast (The house is black), is the best known. It has been recognised as a landmark in Iranian film and a precursor of what we now know as new contemporary Iranian cinema.

[4] Firdusi, Ferdusi, Firdausi or Ferdowsi حکیم ابوالقاسم فردوسی توسی are different ways in which his name has been transcribed into western literature. Born around the year 934 near what is today's Meched (Khorasan), he began writing this book at the age of forty. There was a predecessor, Daqiqi: according to a Book of Kings translated from Pahlavi (old Persian) to Persian (modern Persian) by four scholars from Tus that had started writing this epic, but were murdered after writing about a thousand verses. Ferduwsi incorporated this part written by Diqiqi into his work. Once he completed his Shahanameh, he decided to pay homage to Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna, but the prince gave little in the way of remuneration probably because he did not see the importance of the book.

[5] From a personal interview with Shirin Neshat in September 2009.

[6] SAFFARZADEH, Tahereh. طاهره صفارزاده (Sirjan, 1936 - Teheran, 2008) Professor at Tehran University and Member of the International Writing Programme, she was chosen by the Muslim Centers as the wisest woman in the Islamic world in April 2006 and the Organization of Afro-Asian Writers (OAAW) named her the most outstanding woman in the Muslim world. Saffarzadeh composed numerous poems about the beginning of the Islamic Revolution and translated the Koran into Persian and English. She was critical of new Persian poetry.

[7] MAHLOUJI, Vali is a curator, designer, writer and art critic. Born in Tehran, he has lived and worked in London for 20 years. Responsible for exhibitions and Iranian cinema at the Barbican Centre in London.