ελληνικά

Comme je descendais des Fleuves impassibles,

Je ne me sentis plus guidé par les haleurs

Arthur Rimbaud, "Le Bateau Ivre"

(quoted in the beginning of The Limits of Control)

One painting at a time

Jim Jarmusch, The Limits of Control - CLICK to view trailer

Lone Man visits the Reina Sofia Museum four times to see four paintings: The Violin (1916) by Juan Gris, Nude (1922) by Roberto Fernández Balbuena, Madrid desde Capitán Haya (1987-1994) by Antonio López and Gran Sábana (1968) by Antoní Tapies.

In contrast to most visitors who try to see the entire collection in one visit, Lone Man, standing still, stares at one painting at a time, because he doesn't just want to see, he wants to understand. Each painting becomes an introductory visual note to the next step of his mission, not like a key to a riddle, but more like a reflection of reality, that makes the thing being reflected, the real world, make sense.

The emphasis on the reflection is something recurrent in The Limits of Control. The first image we get of Bankοlé is his reflection on a metallic surface; throughout the film we get glimpses of his figure reflecting on all kinds of surfaces: doors, cars, escalators, windows. The game of reflections, that twists the colors and the shapes of the real world like an artist's paint brush, makes the image less real-like; thus it detaches us from the expectation we usually have when we see a film, that we're watching a real story that should be believable.

"Sometimes the reflection is far more present than the thing being reflected"1; and indeed, if we consider painting and film frames as a reflection of the real world, we see why some of the images in films and visual arts stay so strong in our minds, like lived experience or like "dreams you're not sure you've had".

This is why in this text we shall analyze the thing being reflected, the painting and its influence on cinema, focusing on Jarmusch's Limits of Control and Jean-Luc Godard's Pierrot le Fou, two films that seem like visual poems in motion: successions of shots conceived as visual artworks, adorned with references to paintings and poetic words; the first one beginning and the second one ending with quotes by Arthur Rimbaud.

The painting in the (film) frame

Right: Robert Wiene, Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari | Left: Yakov Protazanov, Aelita (set and costume design by Aleksandra Exter)

Ever since the beginnings of cinema, the moving picture had always followed painting closely. Although a shot is not a painting, it is a découpage of time and space that has been thought about, constructed and composed like a painting2.

Therefore, when filming a shot, a filmmaker works like a painter: he/she has to think about the colors, the composition, the space between the actor and the camera. The results are often remarkably "painterly": from the expressionist mood and surroundings in Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Calligari, to the constructivist sets and costumes in Yakov Protazanov's Aelita -designed by the famous artist Aleksandra Exter- and Theo Angelopoulos' majestic landscapes or Wong Kar Wai's fleeting images, the history of cinema is full of examples of films that are closer to visual arts than to conventional storytelling.

Left: J.H.Füssli, Le Cauchemar | Right: Eric Rohmer, La Marquise d' O

Left: J.A.D. Ingres, The turkish bath | Right: Jean-Luc Godard, Passion

Other times, filmmakers intentionally imitate a famous painting in order to liven up their film frames: Eric Rohmer reconstructing Le Cauchemar by J.H.Füssli for his film La Marquise d' O and Jean Luc Godard reviving Ingres' Turkish Bath for his film The Passion are some well known examples. "Homage, parody or enigma, the shot-painting would always suppose, not just a cultural recognition on the public's behalf, but also a call for reading, deciphering"3.

Even if the original image is unknown to the viewers, it offers a new perspective on the artwork, by placing it into a new context: whereas a painting has no time dimension, the shot-painting is just a moment in a movie, about to evolve into something different when we proceed into the next frame. This sets a new dynamic between the image and the viewer: conventional paintings are still and the viewers move before them; however, the shot-painting evolves and moves before a still audience.

Painting in Jarmusch - The Limits of Control

Jim Jarmusch, The Limits of Control

In Limits of Control, what we have is not a reconstruction of a painting, but the depiction of paintings within the film and film frames structured like a painted canvas.

The viewer is invited to take a close look into the artwork through the eyes of Lone Man, within a new context.

Therefore, Jarmusch doesn't use the paintings to decorate or to illustrate, but to trigger our imagination and to offer a new perspective. As he says, "For me, if something moves me, I get flooded with it. So the idea was that he looks at everything in the way he looks at paintings. The way he watches the nude girl swimming in a pool. There's a scene where there are pears on a plate, and I wanted that to look like a painting. The way he compares the Tower of Gold to a postcard. Even the moving landscapes, when he is travelling by train."

In short, Jim Jarmusch creates a character that views the world through paintings; in addition, the filmmaker creates painting-like frames. It is a constant game of color and composition: Lone Man standing in front of plane monochromatic surfaces (elevators, confined spaces), crossing vivid cities, always wearing the same costume that changes color when he moves on to the next city. Towards the end of the film, Lone Man wanders into the Almeria desert, that offers to Jarmusch's shot-painting an almost abstract background.

The abstractness of the film is enhanced by the story, that gives ground to the strong images that constitute it. The characters don't even have names: the Lone Man, the Nude, the Mexican, the Blonde are just faint figures that appear in the foreground, make their statements on music, films, science, hallucination and then disappear, leaving nothing behind but matchboxes with codes inside. They don't mean to serve a certain plot, just to make an impact. The story is just a secondary element, rather than the driving force; in order to evoke certain moods or thoughts Jarmusch relies on the image -and the music. He lets his camera lens slip on details and take its time as it records objects, explores landscapes. Just a few fragments of reality, weaved with imagination.

When filming a movie, Jarmusch acts like a painter in front of an empty canvas: his films start from visual stimulants -his desire to work in a specific place with specific actors- and incorporate certain images that he has seen or imagined4.

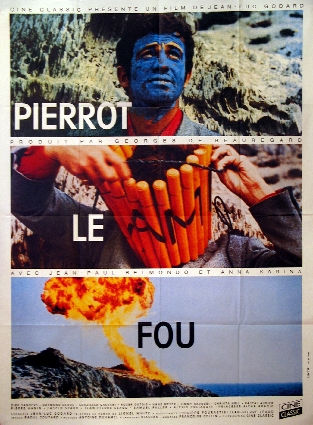

Painting in Jean-Luc Godard - Pierrot Le Fou

Jean-Luc Godard, Pierrot Le Fou - CLICK to view trailer

Likewise, Jean-Luc Godard visualizes his film "starting not from a script or even a story, but from images"5 -and this is particularly evident in Pierrot Le Fou (1965), where the use of the image follows a similar logic to the imagery in The Limits of Control.

Pierrot sets off on a travel to the south of France. However, his wandering doesn't seem to have a specific purpose -it's an escape from his previous life. Crime, love and adventure are things that simply happen, without a previous plan, and trigger his thought constantly, which he expresses through talking and writing. In contrast, Jarmusch's Lone Man sets off on a mission in Spain and every person or incident that shapes his destiny are fragments of a carefully drawn plan; but Lone Man stays silent, listening to other people's thoughts.

A humorous tone in both films comes from the repetition of certain phrases ("My name is Ferdinand", in the first case; "You don't speak spanish, right?" in the second) and an eccentric habit to order for two people (two glasses of beer in Pierrot's case and two espressos for Lone Man). Although the repetition and the unimportant details somehow enfeeble the story, it doesn't matter because in both cases images are stronger than words.

The role of painting in Pierrot le Fou is particularly prominent, either through the reference to classic paintings at the background or through the appropriation of the advances of the painters of the time period when the film was shot.

The second time we hear the female protagonist's name, Marianne Renoir, we see a flash of Auguste Renoir's La petite fille à la gerbe; a few seconds later, above Pierrot's head we see a reproduction of Pablo Picasso's Paulo as Pierrot. Like a painterly reflection, the posters on the walls underline the characters' actions: In one of the film's most famous frames, we see Marianne holding a pair of scissors in front of two Portraits of Jacqueline by Picasso; then she crosses a room decorated with the painter's Girl before a Mirror, before she checks her own reflection in a mirror.

Therefore, just like in Limits of Control, the use of known paintings seeks to provide a foretaste of the subsequent plot and to drive everyday images -of people and places- to the borders of abstraction.

It is right on these borders that some of the most impacting scenes of the movie are conceived and realized: The beginning and the end of the film are marked by monochromatic sequences. In the first minutes of the film, we see Pierrot cross monochromatic frames -entirely blue, yellow, red or white scenes where people seem to levitate in an abstract space.

Left: Jean-Luc Godard, Pierrot le fou | Right: Yves Klein, Anthropometries

Taking into account the fact that the film was shot just a few years after Yves Klein presented his Monochromes (1954), the painter's influence on Godard becomes striking. In the last scene Pierrot paints his face in blue, the International Klein Blue -reminding us of the painter's Anthropometries, where nude models with their bodies painted blue rolled onto white canvases in order to leave their bodily print.

After Blue comes Fire: Klein experimented with Fire Paintings during the last years of his life, where the work was created with the traces of smoke and fire on canvas that had been moistened by female bodies. Just like Klein's transition from blue to fire, Pierrot, after painting his face blue, sets himself on fire. Thus he makes his own leap into the void6 and joins the vast immaterial space: on the last shot we see the sea and the sky blend into an abstract blue frame, as we hear a voice-over of the two protagonists welcoming eternity, with a verse by Arthur Rimbaud:

Elle est retrouvée.

Quoi? - L'Eternité.

C'est la mer allée

Avec le soleil.

Arthur Rimbaud, L' Eternité

(quoted at the end of Pierrot le Fou)

Suggested bibliography:

Pascal Bonitzer, Peinture et Cinéma. Décadrage, Editions de l' Etoile, Paris 1987

Angela Dalle Vacche , Cinema and painting: how art is used in film, Athlone Press, London 1996

Jean Luc Godard, David Sterritt, Jean-Luc Godard: interviews, University Press of Mississippi, 1998

Christina Grammatikopoulou, "Leap into the Void: Wim Wenders' heroes and Yves Klein levitating", Interartive, #5, December 2008, https://interartive.org/2008/12/yves-klein

Ludvig Hertzberg, Jim Jarmusch: Interviews, University Press of Mississippi, 2001

James Roy MacBean , "Filming the inside of His Own Head: Godard's Cerebral Passion", Film Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Autumn, 1984)

Sally Shafto, Leap into the Void: Godard and the Painter, Senses of Cinema, http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/06/39/godard_de_stael.html#1

Juan Antonio Suárez, Jim Jarmusch, University of Illinois, 2007

Filmography:

Jean-Luc Godard, Pierrot le Fou (1965)

Jim Jarmusch, The Limits of Control (2009)

Footnotes:

1 "Sometimes the reflection is far more present than the thing being reflected" and "The best films are like dreams you're not sure you've had" are quoted in Jim Jarmusch's Limits of Control, by the Mexican and the Blonde, respectively.

2 Pascal Bonitzer, Peinture et Cinéma. Décadrage, Editions de l' Etoile, Paris 1987, p. 29.

3 Ibid., p.33.

4 See: Ludvig Hertzberg, Jim Jarmusch: Interviews, University Press of Mississippi, 2001, p.viii.

5 For his film "Passion", Jean Luc Godard asked himself "Could a film be made starting not from a script or even a story but from images?" (see James Roy MacBean , "Filming the inside of His Own Head: Godard's Cerebral Passion", Film Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Autumn, 1984), p. 16). Likewise, in many of his interviews Jim Jarmusch explains how he starts making a film having no more than a few random images in his head.

6 See, Christina Grammatikopoulou, "Leap into the Void: Wim Wenders' heroes and Yves Klein levitating", Interartive, #5, December 2008, https://interartive.org/2008/12/yves-klein