read "Prophets" text

C215, Prophètes. Photo courtesy of Laurence Dentinger GHPS/AP-HP

“Religious tolerance”: those two words were almost the first ones Christian Guémy spoke out, when we talked a couple of months ago, while he was still preparing his exhibition “Prophètes” (Prophets). These two words resounded in my head, while I was facing the challenge to write a text about his new artistic endeavour. And they became tragically relevant, under the prism of the violent events that took place in France only a few days before the exhibition opening. To rephrase Rimbaud, “the [artist] makes himself a seer by a long, immense and rational derangement of all the senses”*. One can only hope that C215’s art, with a distinct message about peace and unity, will somehow manage to heal the shock of hate and violence.

Christina Grammatikopoulou: What is a prophet? Is it someone who sees the future… someone who understands the present better than the rest?

C215 (Christian Guémy): A prophet speaks about the future, but in a language you don’t understand. A prophet is necessarily inspired. He's enthusiastic, literally inhabited by God and a certain vision. A lot of people just consider him as a crazy person.

C.G.: So an artist could be considered as a prophet…

C215: In a way; the artist sees something different from the rest of the world: An artist is supposed to have visions as well.

C.G.: We see a wall, you see a canvas. Like an alchemist, who turns base metals into gold…

C215: Exactly. Art can turn something old and dirty to something of value. Same thing with life : where you only see homeless people, I can sometimes see saints. You usually see saints, when I only see ordinary people. It’s about turning something negative or destructive to something positive. Art is always a certain kind of Magic. A transformation of matter, of light.

C.G.: What is the role of light in the installation “Prophets”?

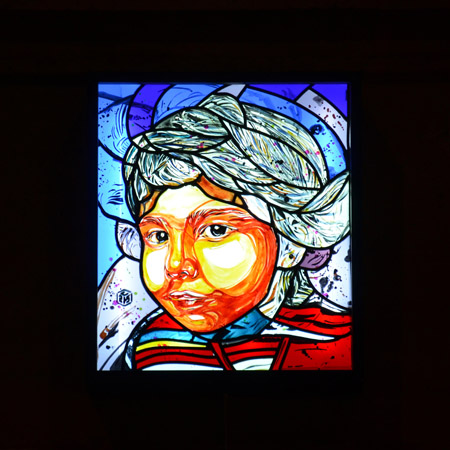

C215: In my art I try to explore constantly new mediums. First it was painting white on dark surfaces, then it was an exploration of colour and for Prophets I wanted to explore the light as a new medium. The stencil is based on a surface which is cut, in a way that it allows light to pass through. There are stencil artists who have been doing light projections through stencils. Instead, I thought that it would be interesting to use light boxes that illuminate space, in a similar way with stained glass windows. It is a way of remixing something that has been used in the past, stained glass, with a more contemporary medium, stencil.

C215, Prophètes. Photo courtesy of Laurence Dentinger GHPS/AP-HP

C.G.: What is the relevance between stained glass art and stencil art? How do these elements “interact” within the church space?

C215: The window glass is interacting with the content of the exhibition in a way that is similar to how the stencils interact with the urban space, the walls, the graffiti and the tags that surround them. In glass windows, just like in stencils, what is important is not the frame, but what goes through it. You only see a light and you cannot see the design in detail. On the other hand, contrary to stained glass, that requires the sunlight to pass through, these light boxes have their own light and require darkness in order to shine.

C.G.: Seeing this in a religious context, one needs to remember that in the past, the stained glass windows or the painted walls of the church were seen by the devout as openings into a different world, the world of God.

C215: This is true. The subject of light is very closely linked to religion. Light is the greatest creation of God and the main celebrations of Christian faith, like Christmas and Easter are linked to the solstices of winter and summer.

C.G.: Considering the fact that these celebrations substituted previous Roman and Ancient Greek celebrations –like Saturnalia- one could say that the concept of light is related to religiousness in general. So what is your position towards religion?

C215: I consider myself a Catholic and I accept the Christian dogma as a part of my history and my culture, keeping in mind however that a lot of things should be seen in a different context, in a more metaphorical way. If you stick to the essence of religious faith, you get the simple rule that you need to love yourself as the others. Love is the real light. Hope as well.

C.G.: In this sense, most religions if they’re seen from a non-fanatic’s point of view speak about love. But the question is, do you think that exhibiting in a church could encourage people of a different faith to enter a space connected to Christianity, somehow abolishing the religious “barriers” between people?

C215: For sure, everyone is welcome to visit the church and view the exhibition, regardless of religion. As for the people who would have certain inhibition to do so, they can still visit one of the light boxes that is displayed outside the church, on the wall of the City Hall of the 13th borough of Paris, creating thus a “universal” space, which acts in a different way from the religious space of the church. Maybe for me, as a street artist, it is even more important to see the reception of this one piece, than the rest of the light boxes that will be in the church, because these ones will be displayed in a segregated space.

C.G.: So, in a way, you overcome the limits between public and private space, religious and secular places. How will this light box fit into its surroundings?

C215: Every night, along with the city lights, the light box will be turned on, but it won’t be an advertisement; it will be a work of art installed on a public building. An interesting element is that nowadays in Paris there are new laws that restrict the use of light signs, in order to turn the city darker and decrease light pollution. The City Hall of the 13th borough is a 19th century building. The light box is a permanent installation on the most modern part of the building, which has no windows. Every night the light box will be turned on, and will light every night coming out of nowhere, from a blind wall, out of the wall, from the inside to the outside, as a symbol of tolerance.

C.G.: This symbol of tolerance is the portrait of a child –just like in the rest of the light boxes- shining onto the viewers, in a similar way as your other portraits of children that shine through the dirty city walls. In what way do you think that these children can bring people together?

C215: It is an interesting observation to see the children as sources of light. My wish is to bring people together through my art, instead of dividing them. Therefore, I wanted to choose a symbol that anybody in the world, regardless of ideology, could agree upon. The most common thing we have as human beings is that we love our children. So, instead of taking a religious symbol from twenty centuries ago, I merged the traditional context with a contemporary iconology: I chose a child from the favelas as a symbol of hope for the future. This kid could be yours. We don’t know his name or anything about his family, his life and his destiny, but he becomes a light in the night. This person is not a Messiah, he could be the exact opposite, since we don’t know what will happen to him in the future. Part of the role of the portrait is to try to see the future and what this person will become. So we want to propose a vision for the future, giving a universal message about hope –because what is faith, if not hope, freedom and love.

C215, Prophètes. Photo courtesy of Laurence Dentinger GHPS/AP-HP

C.G.: This child from the favela and the other children you paint come from different cultures and social backgrounds. We don’t know who they are, yet they have their own distinctive identity, expressing it through their eyes and the way they look back at the viewer.

C215: Indeed, in my work I look for reality and identity, this is why I work with specific people. My art is anthropocentric; every person is a world, a place, a cosmos. Everybody is a mystery, with a certain divinity. I want to give this through my art as a symbol of a new iconology. I want to put people in the centre of the world.

C.G.: In relation to this anthropocentric viewpoint, I remember you once said that you make your artworks in a small scale, because you don’t want to impose your presence in the street, you want people to look for you, in order to find you –in contrast to a number of street artists who establish their name by making big pieces.

C215: I make things small, because I don’t want to make something that looks down on you. I want to paint something in human scale that looks up to you, so that there is an equilibrium between the artwork and the people who see it. It is an anthropocentric point of view that comes from a modest artistic attitude. It’s not about my works catching you, you need to look to find them.

C.G.: You said before that through “Prophets” you want to propose a vision for the future. Looking into those children’s eyes, one cannot help but wonder, what happens to these kids? Do you ever think about that?

C215: Certainly, after travelling a lot and seeing the reality in different parts of the world, I am always worried about the kids. This is why I try to follow up on most of the children I’ve met and portrayed. A lot of the children I’ve painted years ago are now older and keep contact with me through Facebook. A computer screen is also made of light...

C.G.: So can you tell what kind of impact your art has had on them?

C215: I can’t be sure what will happen between me and these children within the next twenty or thirty years, but I assume that the contact with my artwork will mean that they become familiar with a certain ideology that lies beneath it. This is true for street art in general, my art and of other artists that share the same ideology. Imagine that there are children in their teens that follow my work closely, without having access to the Internet, just from seeing it on the street. The gradual familiarization with these images, coming from a direct daily contact, can have a big influence later on, when they become thirty-five or forty.

C.G.: Before you talked about how you interact with the people you portray through Facebook. During the last years, street art has become very popular, partly due to the Internet and the diffusion of images through social networks, somehow making up for the “ephemeralness” of these artworks, that can be destroyed right after their creation. What can you tell us about your presence online?

C215: My work is about taking samples of reality, creating an artwork and then sharing it through the media and the Internet. So, the camera is an important tool. There are photographers who are specialized in making good pictures of street art, but my main focus is to create the work and to share it online. As for my presence on the Internet, I could say that it is similar to my presence in the art world. Just like my artwork is meant to be shared in the streets and not to be exhibited inside galleries, in order to create a direct interaction with people, on the Internet I share my work through social networks only –like Facebook and Flickr- where I can interact with people online. In other words, you will not find a website dedicated to C215, like a “shrine” to my work.

C.G.: So, your main focus in both cases, in street art and online presence, is interaction.

C215: I am an artist who works in public space. In my opinion, there is “street art” but not “street artists” –or at least I do not define myself this way. As I work with street art, my main interest is the interaction between my works and the public in the context of a public space. The basis of my works is the public installation. I work with stencil because I want to be able to act in freedom, without getting commission or asking for authorization before working in the public space. And freedom is the main subject of my work; hope, freedom and unity.

C215, Prophètes. Photo courtesy of Laurence Dentinger GHPS/AP-HP

C215’s exhibition “Prophètes” is open to the public from March 22 to April 30, 2012

at the Chapelle St Louis, Hôpital de la Pitié Salpêtrière, 47 boulevard de l’Hôpital, 75013 Paris. Opening hours: Monday to Saturday 10.30 to 13.50 and 15.40 to 17.40, Sunday 10.30 to 13.50.

For more info contact: Galerie Itinerrance, www.itinerrance.fr, mail: contact@itinerrance.fr, telephone: +33 (0)6 19 98 06 33

[*] « Le Poète se fait voyant par un long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens ». Letter from Rimbaud to Paul Demeny, 15 May 1871