The power to educate or to seduce, to heal or to scare, to tame or to arouse, to unite or to divide...

From cave murals to digital pictures, images have always had a profound impact on human thought.

Hence, they’ve been often seen as carriers of ideas, used by the political or religious leadership in order to propagate ideologies and direct the masses towards one direction or the other.

It is quite difficult to define what transforms an image into a subject of worship. However, by comparing different images from religious iconography and contemporary art, one can see that the difference between the holy and the profane, the religious and the secular lies in numerous factors, such as composition, colors and lines, level of abstraction, subject, cultural references and most importantly, the perception of the art object by the public.

… Restrictions on medium and content

It is also important to remember, that the holy and the profane also depend on pictorial traditions and prohibitions: the ancient Greeks sculpted their gods into images of ideal beauty, whereas the Egyptians engraved half-human half-animal omnipotent deities.

Orthodox Christians distanced themselves from ancient paganism by abandoning sculpture and focusing on painting -rejecting, however, the lifelike quality of ancient art in favor of mannerism.

Islam, on the other hand, prohibited the depiction of human figure altogether and opted for abstract images inspired by nature and calligraphy. When turning the Christian churches into mosques –a standard practice during Ottoman Empire, just like Christians had occupied pagan temples before– they’d often take the eyes off the saints on the frescoes, an action that could be interpreted as a "precaution measure" against any potential metaphysical power of these images.

Ethereal renaissance frescoes, theatrical Baroque altars, wooden totems, marble Buddhas, ivory African masks… art has always had the power to dissolve matter or to transform it into an object with meaning, soul, spirit.

… Relevance of context and perception by “pilgrims”

A power that has not waned with the secularization of art.

Because the art object is –still- a somehow magical object, with the power to stir human thought and trigger revolutions. Its scope of interaction begins with the very space surrounding it. The space hosting an art object can bestow (or remove) the quality of “art” to an object or activity: a urinal turns into a sculpture, when it’s placed in an exhibition space, whereas a famous violinist is ignored like any common street musician, when he decides to play in a metro station.

Left: Marcel Duchamp's Fountain at the MNAC (photo by Jose Téllez), Right: Joshua Bell playing the violin at a metro station (click to view video)

This means that the public’s expectations and cultural background are essential in the perception of an art object as something “majestic”.

The way people interact with these objects is important as well: usually they enter an art space making a minimum of noise, respecting the “do not touch” signs -as they would enter a temple. Still, if they are allowed or encouraged to touch the artwork or interact with it, they are eager to share some of its magic, either by participating in the creative process or by taking pictures alongside the artworks.

If we consider the fact that some museums and art institutions are promoted as a “must see” by the tourist industry, encouraging hordes of tourists to queue for hours to see them, as well as the physical effort implied to see a series of art exhibitions[1], we could view these tourists as art pilgrims: some of them are true believers –or art lovers in our case- but most of them just cause damage with their massive presence and careless attitude; just like the pilgrims that worship Icons or statues, eventually wearing them off by touching or kissing them.

Right: The queue outside the Louvre, Left: Leonardo's Mona Lisa visited by crowds of tourists

… Nonfigurative art worship

In other words, admiring (or worshipping) an image is not always relevant to what it depicts, but to what it stands for or how it is projected.

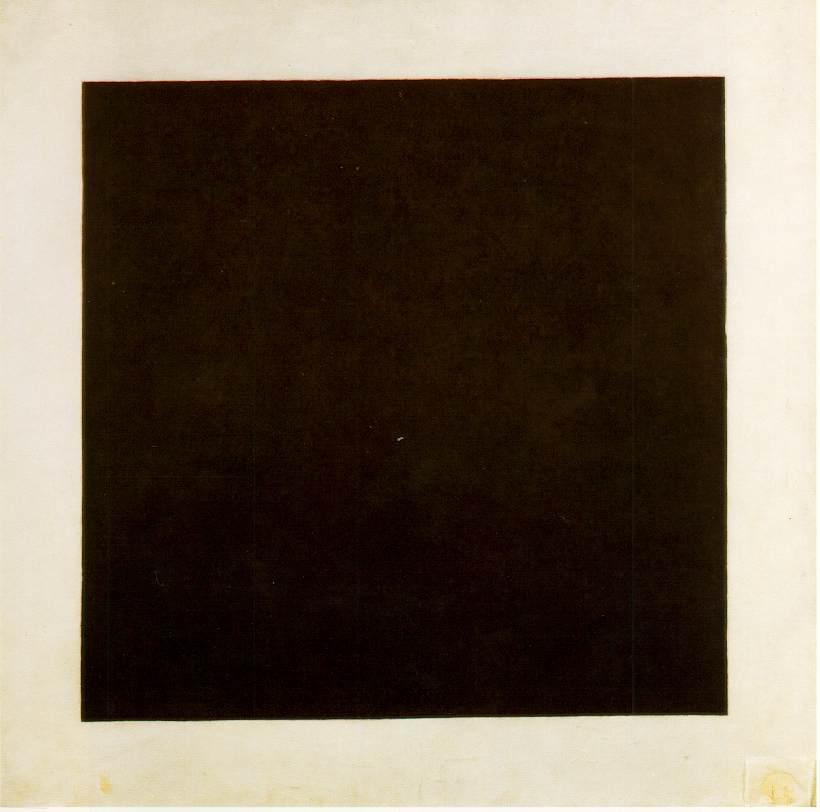

As mentioned above, Muslim religious art tradition was focused on abstract imagery, but was still perceived as something "sacred", not to be worshiped, but to be respected as such. On the other hand, the colorful Orthodox Icons, which would remain behind the smoke of church candles for centuries, would often be transformed into nothing more than a black surface. Still, the devout worshipped them, because they knew how to recognize something sacred in a completely abstract image.

The relation between abstract constructivist images and russian icons has been much documented in art exhibitions and theoretical texts[2]. Even when the abstract forms don’t have a religious origin, they have a mystical force of their own, which is not relevant to what they hide or should be depicting, but to the psychological impact caused by surfaces and shapes of color. It's a common observation that standing before a Rothko or a Pollock arouses a feeling of devoutness, a sense of awe even for people who are not at all religious. It stems from the pure spirituality of these images.

Left to Right: Kasimir Malevich, The Black Square, Jackson Pollock, Number one, Mark Rothko, Red and Black

… The role of composition in creating iconic images

Therefore, composition plays an important role in the perception of an image as "classical" or "religious". When it comes to creating iconic images in figurative art, the composition is of prime importance. These images, which are perceived as a symbol of an idea, often reverberate the composition of well-known paintings that the public is already familiar with.

For example, the idea of a woman standing out from a revolted crowd, as in Delacroix's Liberty leading the crowd, was deliberately recreated in the photograph by Jean-Pierre Rey in order to create a symbol of liberty for May ’68.

![]()

Right: Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, Left: Jean-Pierre Rey, Marianne of '68

Other times the resemblance is coincidental, as in the photograph of Che Guevarra lying dead: a historical moment is captured in a composition similar to the Anatomy lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp by Rembrandt, and reminiscent of renaissance paintings of the Lamentation of Christ. Despite the fact that Che lies among his killers and not a lamenting crowd, the classical composition adds to giving the impression of a martyr.

Right: Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, Left: Che lying dead among his killers

… Religious imagery hits the streets

The composition of religious art paintings has had a significant impact on contemporary culture -a subtle yet important influence when it comes to the popularity of an image or its perception. This influence is a lot easier to recognize in images where the subject or the style of the artwork are directly linked with the religious pictorial tradition.

In most cases, when contemporary art deals with religious subjects, it becomes a subject of controversy, as is the case with works like Asperges me by Thierry de Cordier, which showed a penis ejaculating on a cross, or Piss Christ by Andrés Serrano, a photo of a crucified Christ in the artist’s urine; both works were subjects of vandalism and caused protests against the artists.

Left: Thierry de Cordier, Asperges me, Right: Andrés Serrano, Piss Christ

Yet what is more relevant to see here is how religious subjects are transformed to create contemporary Icons -which is why we shall focus on street art, that often appropriates images and techniques in order to spread its messages across the city.

Angels, devils, crosses, saints, have escaped the limited space of the church walls, and now fill the walls of the city, turning it into a giant temple of art. However, in this temple, worship is hardly ever the issue: street artists merely appropriate images from the religious tradition in order to make a statement about urban life.

This is the case of Christ with shopping bags by Banksy, where the classical image of Crucifixion has been transformed into a comment on the effects of consumerism -leaving it unclear whether Consumerism is the religion Banksy's Christ died for, or the force that has killed him.

In a stencil in Naples, Banksy’s Angel looks like a Renaissance painting, except that he’s not guided by the divine light, but by a gun –an eloquent comment on street violence.

Orticanoodles often uses the face of Jesus –as acted by Robert Powell- in different compositions. One of the most popular ones is a stencil of Jesus in a pier in Brighton, right beneath a railing; the use of the rusty wire as part of the composition turns the stencil into a sarcastic comment about the decadence of urban architecture that limits and wounds our life in the city, like a crown of thorns.

From Left to Right: Banksy, Christ with shopping bags, Banksy, Angel stencil in Naples, Orticanoodles, Jesus stencil in Brighton

Apart from subject, the style of a street art work can also resonate elements from religious iconography. A characteristical example is Bizare (Stelios Faitakis) who is inspired by Byzantine painters and incorporates the mannerist style of orthodox icons in monumental murals. With his works, he manages to create religious painting in a new context, directly related to contemporary life.

Bizare (Stelios Faitakis), Wall painting in Miami (left), Wall Painting in MOCA LA, Art in the streets

If we focus on street art style, we’ll often find a striking resemblance to religious art of the past, especially in stencils; up to an extent, this could be related to the technique itself. Just like church stained glasses, where surfaces of vitro are held together by iron frames, stencils are created from cuttings -where the surface that is subtracted from the carton is filled with color, whereas the carton that remains outlines the colored surfaces like a frame.

A valid example of this is the art of C215, where expressive faces impose themselves on the passersby and the streets. The tired faces of the less fortunate are portrayed in majestic stencils as if they were contemporary saints, whose martyrdom is poverty, loneliness and despair.

C215, Stencils in Barcelona (left) and Milan (right)

... Pop icons to be worshipped and “obeyed”

In other words, the style and technique are important when it comes to constructing Iconic portraits. Andy Warhol's Marilyn and Mao -or any celebrity images that he'd print in series of different colors- consist of bold lines combined with plain surfaces of color. The features of the portrayed person are still recognizable, yet generalized to the point of abstraction and usually limited to two dimensions.

Andy Warhol, Mairilyn (left), Mao (right)

The approach is contemporary; however, the idea is very old. Byzantine artists sought to create "Icons" by rejecting the illusion of the third dimension and by constructing portraits with geometrical features. In other words, they wanted to combine the features of the human face or body, in a way that followed human anatomy, but wouldn't create the illusion of a real person. The golden background and the endless repetition of the same features were also important in turning these handmade pictures into eternal Icons, symbols of Godliness.

Following the same principles, an image of a smiling man, narrow-faced, geometrically-shaped and in an abstract background, has turned into an Icon of Revolution. The Guy Fawkes mask, from the representation of a 16th century revolutionary, went on to become the face of the main character in V for Vendetta –a comic book by Alan Moore[3] that has also been adapted in film. From there it was adopted by the Anonymous, a group of hackers fighting for freedom on the Internet, and subsequently was worn by numerous demonstrators worldwide during the past year, as a symbol of protest and revolution.

Left: Alan Moore and David Lloyd, V for Vendetta (comic), Right: Anonymous in Spanish protests, May 2011

The Anon mask somehow combines the arguments mentioned above, about how an Image can turn into an Icon: elements such as cultural references, geometrical features, abstract background and most of all, perception as a symbol of an idea, are particularly prominent; even more so, in the V.END.etta stencil by Alex de Querzen the Iconic character of the mask is stressed by the golden background. From the pages of the comic book, the Guy Fawkes mask gains the status of a byzantine saint or god, shining in all his golden glory.

Left: Russian Icon, 12th Century, Right, Alex de Querzen, V.END.etta

On the contrary, Obey Giant is an Icon without an Icon, propaganda without a subject. Thus, by stripping the medium from the message, Shephard Fairey reveals the mechanisms of "making an Icon" and the mechanisms of propaganda. In 1989 Fairey took a random picture from the newspaper with the boxer André the Giant and started posting copies of it throughout the entire world, with the word “Obey” printed underneath. Obey whom? Obey what? According to the artist:

“I put these works on the street in order to send some static interference out into the world’s sea of images and messages. The images I use include historical propaganda, black power, parodies of authority, and tweaks of popular culture icons. What’s the point? Well aside from satisfying my compulsive need to produce art, these posters are designed to start a dialogue about imagery absorption. Powerful and seductive images have historically been used for a variety of reasons, some noble, some sinister, some both, depending on subjective interpretation. My work uses people, symbols, and people as symbols to deconstruct how powerful visuals and emotionally potent phrases can be used to manipulate and indoctrinate.”[4]

As in the Anon mask, here as well the order to “Obey” is a reference to a film, John Carpenter’s They Live, where the protagonist reads messages hidden in the billboards. However, in Fairey’s art the image is far stronger than any written word. A few years after he started the “André” propaganda the artist omitted the “Obey” slogan altogether. André’s face turned into an authority figure, ordering us to “obey” in silence.

Shepard Fairey, Obey (left), Sage Francis (centre), Obama (right)

Combining elements from old Soviet posters, war propaganda, political campaigns and strong references to known artworks, Fairey managed to create a successful campaign, which spread art images throughout the world.

In 2008 the artist made an Iconic portrait of Barack Obama. The face expression of the president, looking above, as well as the style of the portrait, limiting the color range to the colors of the American flag, with only one word underneath, “Hope”, “Change” or “Progress”, communicated a very strong message to the public, who went on to vote for Obama. Soon the Obama poster became extremely popular and numerous variations appeared –even online applications that can turn your face into an Obama-like poster.

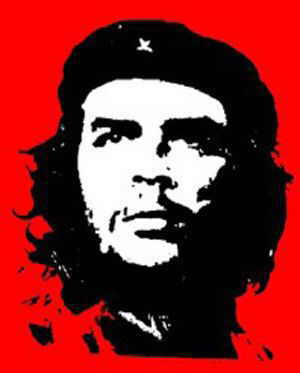

The popularity of the Obama poster is linked to Fairey’s influences for the creation of the image. As it has been widely recognized, the poster is a contemporary adaptation of the most famous photograph of the 20th century, the Guerrillero Heroico by Alberto Korda. The photograph of Che Guevarra has been transformed into a mostly popular poster by Jim Fitzpatrick. The iconic image has been reproduced innumerable times: it has been painted, printed, tattooed, sculpted, transformed in any way possible, sometimes even exploited in ways against the ideals of the revolutionary. Still, Che’s calm decisive look towards the sky, to the imminent immortality, transforms him into an Icon beyond time and space.

A timeless, universal saint.

Suggested Bibliography:

Robin Cormack, Byzantine Art, Oxfort University Press, 2000

Shepard Fairey, “Question: Education or Exploitation? Manufacturing Dissent”, Text originally published in Tokion Magazine, online at http://obeygiant.com/essays/question-education-or-exploitation-manufacturing-dissent

Alan Moore and David Lloyd, V for Vendetta, Series published by DC Comics, 1982-1989

Hans-Bernard Nordhoff (ed.), When Chagall Learnt to Fly: From Icon to Avant-garde, (exhibition catalogue), Legat-Verlag 2005

Miltiadis Papanikolaou (ed.), Behind the Black Square: Texts and Speeches, State Museum of Contemporary art of Thessaloniki, 2002

Lucila Vilela, “El desespero contemplativo”, Interartive #8, December 2008, https://interartive.org/2008/12/turism-art/

[1] See also: Lucila Vilela, “El desespero contemplativo”, Interartive #8, December 2008, https://interartive.org/2008/12/turism-art/

[2] See, for example, Hans-Bernard Nordhoff (ed.), When Chagall Learnt to Fly: From Icon to Avant-garde, (exhibition catalogue), Legat-Verlag 2005.

[3] Alan Moore and David Lloyd, V for Vendetta, Series published by DC Comics, 1982-1989

[4] Shepard Fairey, “Question: Education or Exploitation? Manufacturing Dissent”, Text originally published in Tokion Magazine, online at http://obeygiant.com/essays/question-education-or-exploitation-manufacturing-dissent