During the protests following the May 2020 killing of George Floyd, various monuments were removed or plans for removal were announced. Removals focused on monuments to the leaders and the military of the Confederate States of America, an unrecognised republic formed by secession of seven slave-holding states existing from 1861 to 1865. In some cases, monuments were removed by the city in an official manner, as the Confederate War Memorial in Dallas, Texas (fig. 1). In some others, monuments were toppled by protesters, as the Statue of Albert Pike in Washington D.C (fig. 2).

Fig 1 - The Confederate War Memorial in Dallas (1897) commemorates soldiers and sailors from Texas who fought with the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. In February 2019, the Dallas City Council removed the monument and place it in storage. Creative Commons license.

Fig 2 - The statue of Brigadier General Albert Pike, a senior officer of the Confederate States Army. The memorial was unveiled in 1901 in the Judiciary Square neighbourhood in Washington, D.C. Protesters toppled and burned the statue in June 2020 in response to the killing of George Floyd. Creative Commons license.

Several municipalities had already started to remove Confederate monuments in the wake of the June 2015 Charleston church shooting, when a white supremacist shot to death nine African Americans attending a Bible study session. The momentum had accelerated after the Unite the Right rally in August 2017, a white supremacist and neo-Nazi rally aiming to unify white nationalist movements in the US, while opposing the removal of the Confederate statue of General Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia.

During the George Floyd protests, the focus expanded to include more statues that were seen as celebrating slavery and racism. For example, many statues of Columbus were removed in the US, as his arrival on the American continent symbolised the beginning of colonialism and genocide of Native American people. Protests extended to other countries: in Belgium, a statue and some busts of King Leopold II were officially removed for the atrocities committed during his rule in the Congo. In London, the statue of Winston Churchill was spraypainted with the words “was a racist”, and became an object of debateabout whether it should be removed from Parliament Square. In Italy, a long-lasting debate erupted again on whether to remove the statue of Indro Montanelli, an Italian journalist and historian who came under scrutiny for his fascist and colonialist past during his youth. Montanelli also fought during the Eritrean War, during which he bought and married a 12-year-old Eritrean girl, whom he often called “a small docile animal” on several occasions.

These recent controversies on monuments can be added to hundreds more that have addressed the public display of totalitarian built forms in the past. Monuments in post-Soviet countries that have survived as legacy of the Soviet regime still create controversies. As soon as possible, new-born post-Soviet elites undertook several initiatives to marginalise, remove and relocate them in several ways. Legal means were used in some cases: for example, the 2015 Decommunisation Law in Ukraine opened the way to dismantle Soviet monuments and symbols; a similar law was amended in Poland in 2017 to make legal the removal of Communist war memorials by the end of the same year. Removals have also occurred in unofficial ways: right after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the spontaneous tearing down of Soviet monuments was a noticeable sign of regime change. Even more recently, unofficial manipulations occurred in post-Soviet and post-Socialist countries: for example, during the night of 24 February 2014 in Sofia, a street artist daubed paint on the 1950s Monument to the Soviet Army, transforming the represented soldiers into pop culture characters such as Superman, Captain America, Wonder Woman, Joker, Santa Claus and Ronald McDonald, in solidarity with the Euromaidan revolution against Ukraine’s pro-Russian regime.

Controversies over monuments can also be found in countries where transition to democracy was less recent than in post-Soviet countries. On 5 October 2017, the editorial on the New Yorker by Ben Ghiat raised the issue on “Why are so many fascist monuments still standing in Italy?”. As Panico (2019) explains, Ben Ghiat was highly criticised for wanting to tear down all the Fascist built environment. The mediatic impact of this editorial contributed to create an ongoing public debate on the conservation of the urban legacy of Fascism.

There remains the question how to deal with controversies around monuments. While being aware there is no single recipe or fixed formula, this paper aims to give a tentative answer to this question. To do so, it first describes what monuments are, in order to explain why they so often become subjects of controversies. It then goes on by introducing a typology of common strategies to culturally rehabilitate monuments in transitional societies and beyond. Finally, it provides two solutions to deal with controversial monuments.

1. What, really, are monuments?

Monuments exist in many different forms: war memorials, public statues, monumental buildings, memorial gardens and even entire areas of the city. They can be of various sizes, made of different materials of constructions, have different shapes and colours. They are mostly located in the city, but they can be found even in villages or in the natural landscape.

What is common among them is that they have both commemorative and political functions. While articulating specific historical narratives, monuments convey the specific worldviews of those in power. As such, they necessary encompass a whole set of meanings, identities and events, while wittingly or unwittingly concealing others. Therefore, monuments define what and who is to be remembered of the past, as well as what and who is not. National elites and their affiliates are aware of the power of monuments and use them as tools to legitimate their political primacy. Through them, elites can shape and spread dominant worldviews, reinforce political power and set off social dynamics of inclusion and exclusion.

However, individuals interpret monuments in ways that can be different or even contrary to the intentions of those who have them erected. This is the paradox of monuments: they are meant to be stable over times in their physical forms, but their meanings are dynamic, reflecting changes in culture, social relations, concepts of nation and views on the past. For this reason, monuments representing outdated cultural values or the worldviews of previous regimes often become controversial and their permanence in public space problematic.

In practice, monuments can assume different functions as time passes. Monuments legitimising elite power can turn into sites of resistance politics: for example, after the fall of the Soviet Union, popular movements suddenly used Soviet monuments to demonstrate against the same regime that installed them. Otherwise, people can scorn or ridicule monuments that are sacred for elites: Romans ironically attach the name “the typewriter” to the Vittoriano, a huge monument in Rome commemorating the first king of united Italy (Atkinson and Cosgrove 1998, fig. 3). In a less spectacular way, monuments can turn into neutral landmarks attracting everyday activities, such as inattentive crossing, meeting, eating, playing and so on.

Fig. 3 - The Victor Emmanuel II National Monument in Rome, also known as Altar of the Fatherland, was inaugurated in 1911 to honour Victor Emmanuel II, the first king of a unified Italy. Romans ironically call it “the typewriter”. Picture taken on 18.07.2020

In brief, monuments present a discourse of the past designed by an author - in most cases, the national elites and their affiliates - for specific purposes (Violi 2014: 11). However, this discourse is always open to a myriad of interpretations depending on the point of views that the readers take toward it, each one having its particular way to frame social reality based on cultural traits, political views, socio-economic interests as well as contingent needs (Eco 1979).

2.Common strategies to deal with monuments in transitional societies

The semantic changeover of monuments has been evident in transitional societies characterised by regime change. Here, both the redesigning of monuments inherited from the previous regime and the erection of new ones have been potentlyeffective in shaping specific worldviews consistent with new political and cultural situations. The list below presents a typology of common strategies that are being used to deal with monuments inherited from a previous regime, each with its own symbolic, cultural or political aims. The practices described here are strictly analytical categories, and therefore, not every monument can be seen to fit neatly into one or the other. Moreover, each monument may have been invested with more than one of these resemiotising strategies at different times.

Leaving the monument as it stands

The monument is left exactly as it was intended by its owners, without using any manipulation of its immediate surroundings. In this case, monuments have become silent: no one has an interest in either preserving, redesigning or removing them. People generally do not acknowledge their function and do not have any particular sentiment or attitude towards them. No specific urban practice is registered around them, if not inattentive crossing.

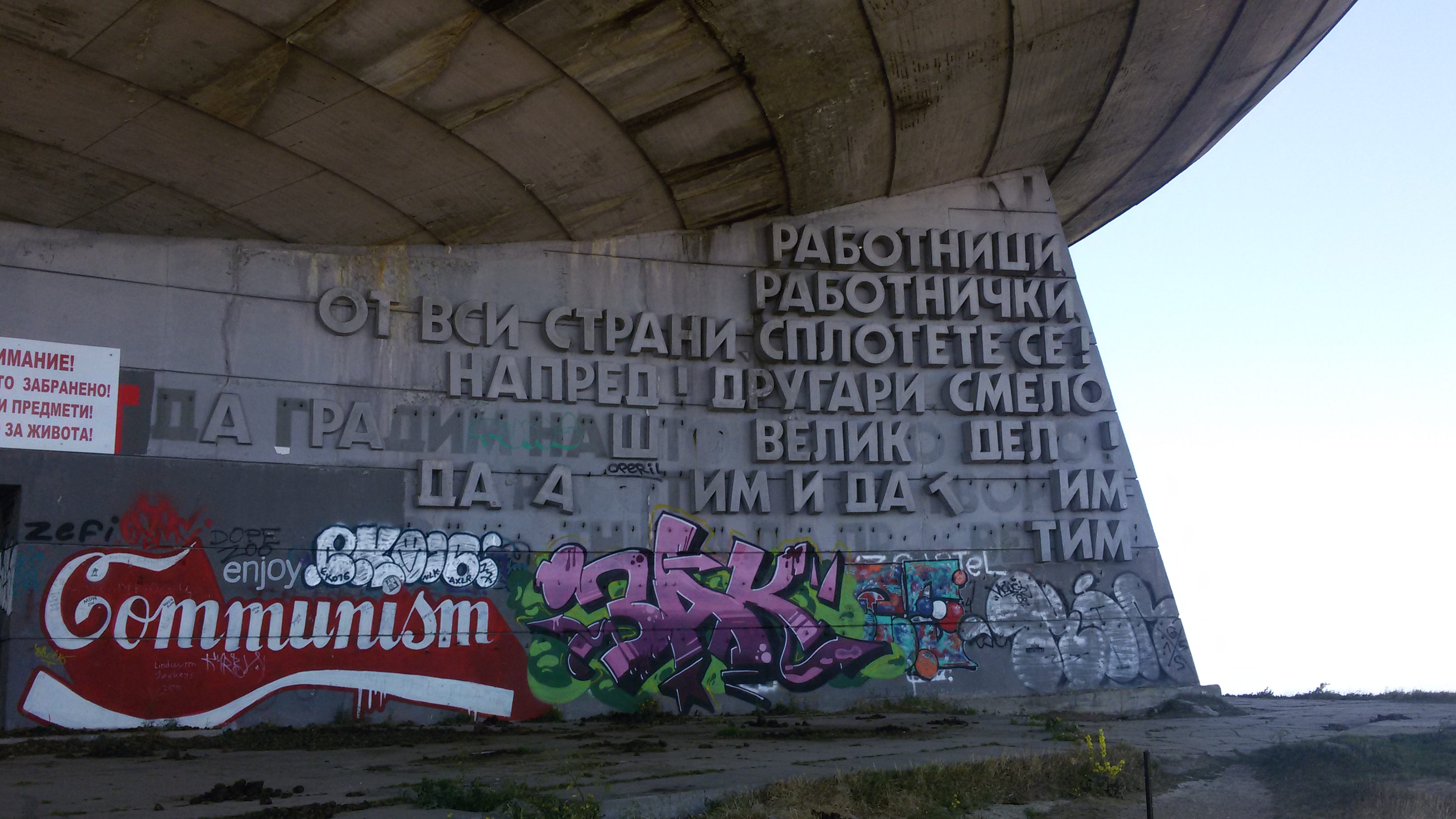

Abandoned monuments can attract unexpected practices that interact with their original meanings. The abandoned Buzludzha monument in Bulgaria was built during the Bulgarian Communist regime in the place where, in 1891, a group of socialists assembled secretly to form a movement that led to the founding of the Bulgarian Communist Party. Today it is a place where graffiti artists do their writings and drawings: in the picture below, one can see a graffiti representing the word ‘Communism’ drawn as the Coca Cola logo (fig. 4). Abandoned Communist monuments also attract some tourists who appreciate their architecture, as demonstrated by numerous publications and websites dedicated to them (e.g. Litchfield 2014).

Fig. 4 - The Buzludzha monument in Bulgaria. Creative Commons license.

Conservation and renovation

In this case the monument is considered as a trace of the past that cannot be erased and has to be conserved as part of the national cultural heritage. Different practices of preventive conservation and maintenance are being provided to inhibit the gradual and inevitable process of deterioration over time. Additionally, renovation can be done to improve damaged monuments and to preserve their appearance and function as close to their original one. Monuments considered worthy of conservation and preservation can be protected through legal means and through national and international organisations such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Even if considered worthy of conservation and renovation, the monument can still be considered controversial by a part of the population. For example, there are several Soviet memorials in Eastern and Central Europe that survived spontaneous destruction after the collapse of the Soviet Union, as for example the Soviet War Memorial in Tiergarten, Berlin (fig. 5). These memorials can be considered a source of traumatic memories by a part of the population that would like them to be removed. However, to erase memorials from the public space is no easy task for various reasons. First, removing monuments costs: finding resources for removal was difficult during the transition from the centrally planned to the market-based economy, and is still difficult today in times of crisis and austerity. Second, removing memorials celebrating events and identities that are still important in the currenthistorical narratives of Russia can provoke fierce reactions by Russia itself, such as the imposition of economic sanctions, trade, diplomatic and cultural restrictions, visa bans as well as cyber-attacks, hybrid threats and warfare. Third, Soviet memorials can still be important sites of commemoration for the Russophone communities living in post-Soviet countries. Removing them often sparks emotional reactions and civil disorder.

Fig. 5 - The Soviet War Memorial in Berlin erected by Soviet authorities to commemorate Red Army soldiers who died during the Battle of Berlin, April–May 1945. Creative Commons license.

Manipulation of the surroundings

The spatial settings in which monuments are located contribute to their interpretations. Often, the surrounding built environment is redesigned to provide appropriate location for future monuments. The manipulations of spatial surroundings have been broadly used also to lessen the visibility of unwanted monuments and memorials. For example, the Estonian government has taken several measures to reduce the visibility of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn (fig. 6), a Soviet memorial which stood in the city centre of Tallinn until 2007.

Fig. 6 - The statue of the Bronze Soldier. Picture taken on 29.10.2015

Adding or removing elements to change the original meaning

Adding or removing material elements to monuments may transform their function. An example from the past are the Greek statues whose private parts were removed or hidden through orders of popes in the Middle Ages, since they were considered publicly offensive and indecent (fig. 7).

Fig. 7 - Statue of Mercury in the Vatican with the fig leaf placed over his privates under. Creative Commons license.

Turning the monument into something else

Here the events or identities represented in the monuments are turned into something completely different. For example, in Odessa, Ukraine, the local artist Alexander Milov turned a statue of Lenin into Darth Vader, the villain of the film series Star Wars. The Lenin statue strikingly suited the form of the new subject: Lenin’s long coat became the cloak of Darth Vader and his closed fist now holds a lightsaber. As seen in the video below, Darth Vader was unveiled during an opening ceremony that included vehicles and characters from the Star Wars: a person dressed as Darth Vader unveiled the statue and held a speech with Darth Vader’s vocal effects. The well-known Darth Vader music theme from the movie played through. The attendees could take pictures of the performance and upload them on the Internet, also thanks to a Wi-Fi access point included into the Darth Vader statue’s helmet.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xeHdRBgVFvM&t=47s

Relocation

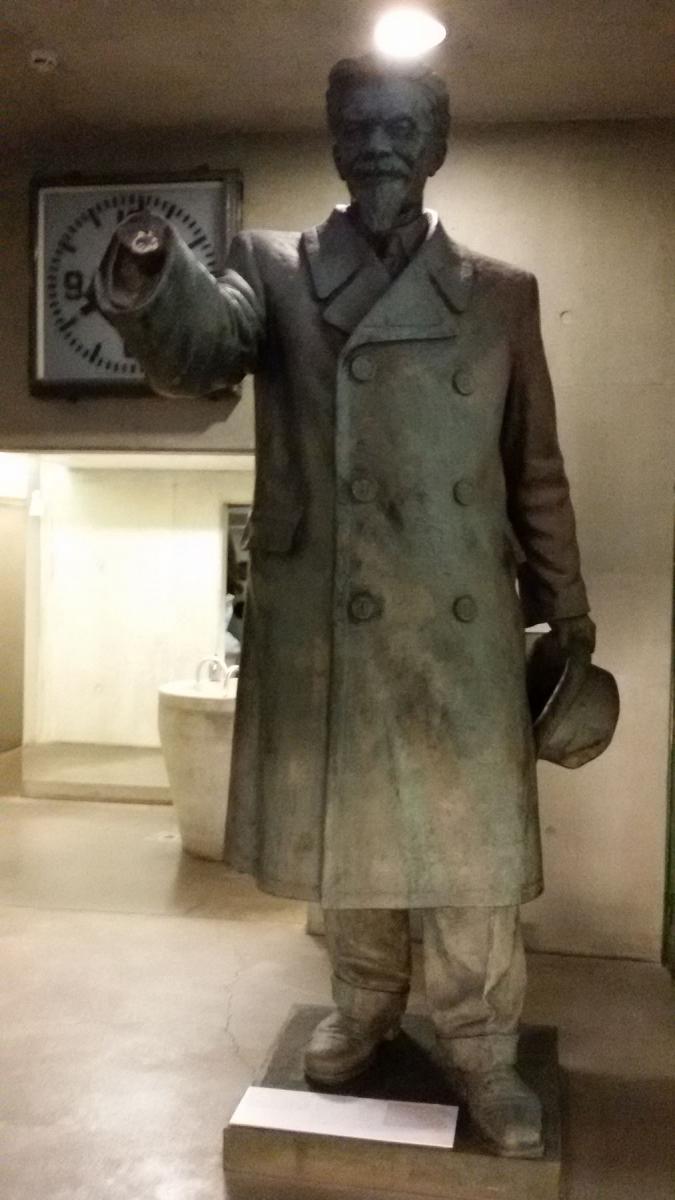

Relocating memorials with site specific connections to the events and people commemorated can partly annihilate its original meanings. To reduce their visibility and symbolism, elites may decide to relocate monuments in a location not originally made to receive them. If a monument becomes controversial, it can be relocated from main tourist sites or highly populated places, as an attempt to define its meanings as alien to today’s dominant culture. Sometimes, controversial monuments are removed from their location and placed in museums, so as for them not to be seen in public space anymore and in order for them to be interpreted in the same way as other cultural heritage. For example, in the USA there is an ongoing debate whether to relocate some Confederate monuments from public places to museums (Bryant et al 2018). However, unwanted monuments placed in museums can receive renewed attention, e.g. from tourists, who visit museums to learn the official history of the country. The Vabamu Museum of Occupations and Freedom in Tallinn opted for an ironic solution placing monuments to Soviet leaders at the entrance of the museum’s toilet (fig. 8).

Fig. 8 - A Soviet statue guarding the toilet of the Museum of Occupation in Tallinn. Picture taken 5.6.2015

Removal

Monuments have often been removed from public space and placed in storage or dumped somewhere in a hidden spot. For example, there was a collection of 15 Soviet-era statues simply dumped in the backyard of the Estonian History Museum at Maarjamäe, Tallinn (fig. 9). In 2017, these statues were assembled into a formal outdoor exhibition, along the lines of other sculpture parks displaying dismantled Soviet statues, such as the Fallen Monument Park in Moscow, Grūtas Park in Lithuania and Memento Park in Budapest.

Fig. 9 - Soviet statues herded together in the yard behind the Estonian History Museum’s Maarjamäe Palace in Tallinn. Picture taken 10.04.2015

As for the monuments removed during the protests following the killing of George Floyd, the removal can be done in an “official” manner, by national and city institutions through legal means, usually being pressured by protesters’ “unofficial” way. Below the term ‘destruction’ is used to define the unofficial practices of toppling, removing and destroying monuments.

Destruction

This is a practice that highlights regime change and symbolically condemns the people and ideals monuments represented. It was for example the first spontaneous reaction after the news of the collapse of the Soviet Union, when people blew up, toppled and knocked down monuments with picks or other offhand tools. For example, the Stalin Monument in Budapest (fig. 10) was torn down by anti-Soviet protesters during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

Fig. 10–The Stalin Monument was erected in 1951 to celebrate the seventieth birthday of Joseph Stalin in Városliget, the city park of Budapest.

More recently, many monuments were spontaneously destroyed during the Euromaidan, a set of protests and civil unrest sparked in November 2013 by the Ukrainian Government’s decision to suspend the signing of an association agreement with the EU (fig. 11). In Ukraine, the spontaneous practices of toppling and destroying monuments have then become formal law in April 2015, when president Petro Poroshenko signed a set of bills to remove Lenin statues and other Soviet monuments as well as Soviet symbols.

Again, during the George Floyd protests in June 2020, a number of monuments were toppled by activists and protesters: for example, the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol, UK was toppled, defaced and pushed into the harbour due to his involvement in the Atlantic slave trade.

Fig. 11 – Protesters toppling a statue of Lenin in Khmelnitsky, Ukraine, 21 February 2014. Creative Commons license.

3.Erecting new monuments and memorials

The strategies described so far aim to reassess the meanings of existing monuments inherited from the past. Simultaneously, national elites need to erect new monuments in order to present in space cultural meanings and historical narratives consistent with current political and cultural situations. A common trend in today’s post-Soviet countries is to build urban decorations free from direct political purposes. Representing everyday meanings, these urban decorations are creating attractive cultural quarters bringing together playful practices, tourism and leisure, while improving the vitality and marketability of post-Soviet cities.

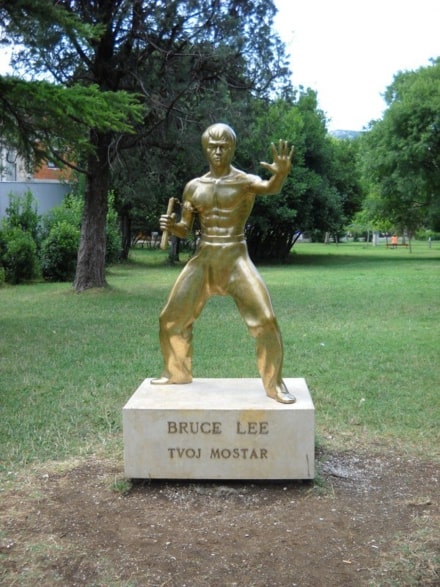

Examples of these of non-confrontational urban decorations have been erected throughout former Soviet as well as former Socialist countries in Europe. Often, they portray characters from popular culture, such as the Bremen Musicians in Riga, Latvia (1990, fig. 12); the bust of Frank Zappa in Vilnius, Lithuania (1996, fig. 13); the Bruce Lee statue in Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina (2005, fig. 14); The Beatles statue in Almaty, Kazakhstan (2007, fig. 15).

Fig. 12 - Bremen Musicians in Riga. Creative Commons license.

Fig. 13 - Frank Zappa bust in Vilnius. Picture taken 16.6.2015

Fig. 14 - Bruce Lee statue in Mostar. Creative Commons license.

Fig. 15 - The Beatles statue in Almaty. Picture taken 5.3.2016

4. Towards a participatory design of monuments

The controversies around monuments across the world indicate that it is impractical for a national elite to create a uniform, collective memory that is shared by the whole of society. Consequently, national elites should consider the multiple nature of memory, that necessarily led to the coexistence of different interpretations of the past, spatial representations and practices of commemoration.

There remains the question: how do we deal with controversies around monuments? There is no single recipe or fixed formula: each case has its own idiosyncrasies depending on the social, political context in which they emerge. However, two solutions can be suggested, if we are to limit abusive debates and toxic social conflicts resulting from ill-advised national politics of memory and identity in transitional societies all over the world.

- Any intervention on monuments – from conservation to destruction, from manipulation to the erection of new ones – has a meaning that can be variously interpreted due to multiple historical narratives and identities that coexist at the societal level. Design professionals should consider the multiplicity of interpretations when approaching the design and the cultural reinvention of monuments. Broadening participation to create the future memorial landscape will at least partly prevent conflicts between different mnemonic communities and parts of society.

To do so, participatory design methods can allow for cross-discipline participations of different experts and professionals such as planners, designers, architects and artists, as well as gauge the opinions of the citizens (Kunze et al 2011). Participating in the design of monuments should not be bureaucratic, but dynamic, agile and resembling the ways in which people communicate and interact today with digital technologies and social platforms.

The role of digital technology in enhancing the participation in monument design as well as in promoting online commemorative practices to broader audiences in more accessible ways will inevitably be an issue in future research and practical planning. Future studies aiming at digital solutions for commemorations in absentia, as those experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, will also need to be undertaken. - Planning and design are inevitably political, but they should not be politics. Escalating tensions for political purposes can lead to the emergence of old and new conflicts dividing population on an ethnic, social and political grounds.

Focusing on meaning, interpretation and cultural space, an interdisciplinary framework connecting semiotics and cultural geography can prove useful towards a deeper understanding of how monuments assume multiple meanings in the context of changing concepts of past, nation and culture. To do so, this approach examines both the perspectives of the designers and of the everyday users, while considering the agency of monuments, i.e. the impact they have on the everyday practices of citizens.

References

Atkinson, David & Denis Cosgrove. 1998. Urban rhetoric and embodied identities: City, nation and empire at the Vittorio Emanuele II monument in Rome 1870–1945. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88 (1). 28–49.

Bryant, Janeen, Benjamin Filene, Louis Nelson, Jennifer Scott & Suzanne Seriff. 2018. Are museums the right home for Confederate monuments? Smithsonianmag.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/are-museums-right-home-confederat... (accessed 3 January 2020).

Eco, Umberto. 1979. The role of the reader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kunze, Antje, Jan Halatsch, Carlos A. Vanegas, Martina Maldaner Jacobi, Benamy Turkienicz& Gerhard Schmitt. 2011. A conceptual participatory design framework for urban planning: The case study workshop ‘World Cup 2014 Urban Scenarios’, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Proceedings of the eCAADe Conference, Ljubljana, 895–903.

Litchfield, Rebecca. 2014. Soviet ghosts. The Soviet Union abandoned: A Communist empire in decay. Carpet Bombing Culture.

Panico, Mario. 2019. Questioning what remains: A semiotic approach to studying difficult monuments. Punctum. International Journal of Semiotics 5 (2). 29–49.

Violi, Patrizia. 2014. Paesaggi della memoria. Il trauma, lo spazio, la storia. Milan: Bompiani.