Italiano

“So I must leave, I'll have to go to Las Vegas or Monaco and win a fortune in a game, my life will never be the same”

Abba, Money, Money, Money, 1976.

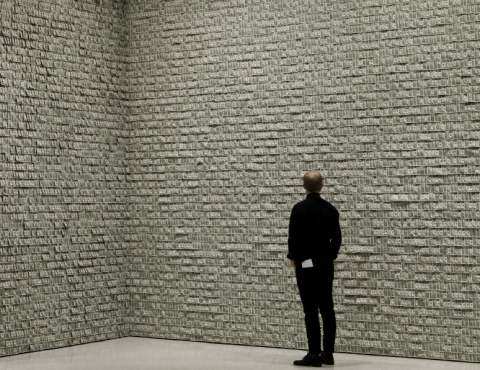

Image courtesy of the Guggenheim, New York. Previously published in the on line magazine Contemporary Art Daily.

The color of money, their smell, texture, weight, size ...

Very rarely do we stop to think about the physical and aesthetic qualities of money, maybe because we are too busy trying to earn it and spend it. We often handle it, we use it as a medium of exchange, we give it, we receive it, and we use it for financial investments, to cure us, to have fun, to travel, shortly, for everything. What we generally define as well-being is permanently and totally related to the value we place on money.

We use clichés like "money does not buy happiness" perhaps under the illusion that we basically do not need it because in our life there are more important things. Happiness, for example. We delude ourselves thinking that we are able to rediscover this feeling in the small and great things of our daily lives: Things that seem to be immune to the power of money like family, love, looking at a starry sky, visiting a museum and finding the same starry sky that we observed during a happy experience, but painted by a famous painter who lived a century ago.

These stereotypes often lead us to treat money with contempt as if it were the bane of our society, this capitalist society that takes us away from pure and true universal values in advantage of the futile and the vain. But money does not hold a power in itself, even a magic that is essentially universal. It is a tool in the hands of all those who own it and have value only in terms of how one uses it. For this reason many of us would do everything to get money, because as Liza Minelli sang in Cabaret, a classic film directed and produced by Bob Fosse in 1972, “money makes the world go around”.

Committed, as we are in seeing money in a metaphorical, metaphysical, economic and political way, we often lose the ability to perceive it from a purely aesthetic point of view. At least until someone decides to exhibit it in a museum. In this case, the money becomes an artistic work.

The German artist Hans-Peter Feldmann was the winner of the prestigious "Hugo Boss Prize" in 2010, receiving the honorarium of $ 100,000. In an effort to separate the influences of our visual surroundings in our subjective realities, Feldmann has spent over four decades producing images and object into serial archives, uncanny combinations, decontextualized out of their common meaning and reusing them in new experiences and creative environments. For the exhibition in the Guggenheim of New York, Feldman decided to pin the entire amount he received on the gallery walls in a grid of overlapping one-dollar bills. The money bills were all placed vertically and attached to the wall only by their top edge, creating an effect of lightness and movement. The aesthetic effect is absolutely amazing, even more so when the viewer discovers that it is real money. Thinking about it, how many people have had the opportunity to enter a room covered with $100,000? Very few, I think. Therefore, the excitement is a normal reaction. Strangely, however, the perception of the bills changes when, unable to take any, the spectator decides to look at them through different eyes: thus focuses on their aesthetic qualities such as the odor, color, shape , drawing, etc.. In the eyes of the viewer the money goes back to being what it really is: paper.

In the exhibition room, one can listen to many comments and easy jokes. Some appreciate the design, created in 1935 under the leadership of Franklin D. Roosevelt and printed by the Federal Reserve since 1929. Others try to touch them when the guards look away or blow over them in order to observe the movement and lightness. Others walk around the room pretending to be totally indifferent, even outraged. But there are those who endorse because, for them, the artist makes a shrewd critique about the note definition of “art and economy”, “art and market”, “commoditization of the art object”, etc..

In a famous movie of Martin Scorsese, the protagonist, called “Fast Eddy” says that "money won are sweeter than money earned". I think, one could agree with this claim. Will this be the reason that led Hans - Peter Feldmann to exhibit money turning it into a work of art?

Subject to a theoretical interpretation, this would need an answer to the question (which seems to be much more legitimate than others): should this money continue to be just an aesthetic element, an art installation that will travel to museums and galleries, or should the artist decide to restore their economic value? Maybe just by selling the work itself, that is, selling the money for more money. He wouldn’t be the first in doing so. Before him, Andy Warhol, showing his work 200 One Dollar Bills said, not without malice: “making money is art.”

However, if it should happen one shouldn’t need the opinion of an expert to know the value of the work... certainly not less than $ 100 000!